What it manages to bring together within the frame of a meager B-film plot is quite astounding, balancing the brutality and atmospheric visuals with the direction of Robert Wise to develop something quite memorable. Boxing movies have been bigger and better, but film-noir has a way of dredging up the grittiest pulp and the Set-Up is that kind of film.

What it manages to bring together within the frame of a meager B-film plot is quite astounding, balancing the brutality and atmospheric visuals with the direction of Robert Wise to develop something quite memorable. Boxing movies have been bigger and better, but film-noir has a way of dredging up the grittiest pulp and the Set-Up is that kind of film.

Its fight sequences are violently staged with human forms evoking the early realist images of George Bellows. However, it’s as much of a backroom drama as it is a fighting film. We see the payoff taking place behind Stoker Thompson’s (Robert Ryan) back as his manager (George Tobias) cuts a deal with the opposition without telling his main man what’s going on. He figures Stoker is all washed up at 35. There’s no way in heck he can beat the young buck he’s up against.

The dressing room is full of has-beens, young guns, and hopefuls who in just a few minutes paint a picture of what the boxing world really is. It’s a cruel game that is sweet in victory and sometimes even deadly in defeat. Still men of all backgrounds and values are drawn to it for one reason or another.

In fact, they are not the only ones. One of Robert Wise’s most formidable allies in this film are his close-ups that ratchet up his drama by utilizing the emotive reactions of his crowd. He builds a cadence introducing each nameless face early on and riding their reactions all the way through the fight. There is the woman who feigns repugnance only to reveal her ugly penchant for brutality. There’s the tub of lard who fills up on every concession imaginable while greedily watching the violence unfold. Then, the nervous husband who is constantly hitting and jabbing a phantom opponent. The list goes on.

We also witness the initial reluctance of Stoker’s girl (Audrey Totter) to go see him get beaten to a pulp. This is more than just fighting–it affects their future life together. And while he gets ready to fight, she listlessly wanders the streets too frightened to watch him get his block knocked off and still not yet empowered enough to change things. All she can manage is a jaunt through an arcade parlor, a few furtive glances overlooking the passing trains, and finally a lonely visit to a midnight diner. But this is hardly casting blame mind you.

The bottom line is that Stoker doesn’t see his girl ringside, and it feels like everyone down the line has abandoned him. There’s a need for vindication–to prove his worth when no one will give him a second thought. And that’s a dangerous place to be when people are betting on you to take a fall compliantly, namely one big whig named “Little Boy.” But Thompson’s not about to do that, fighting until he has nothing left to give. And he wins someway, somehow.

It’s when he gets ready to leave the building after the crowds have filed out and the trainers have left for home, that he meets an ominous welcoming committee. It’s not an unsurprising conclusion, but still, Thompson’s story finds a silver lining amidst all the violence. This film is a miracle of the studio age and Wise makes it an incessantly interesting piece of noir.

3.5/5 Stars

You can take Animal House one of two ways. Either it glorifies fraternity life to chaotic proportions or it’s a satirical mockery of the collegiate institutions. Either way, the film works, because the bottom line is that it has laughs. Sure, some of them take hold of nostalgia while simultaneous instigating the trend towards crude, gross-out humor, but Animal House has some generally uproarious moments of mayhem to match some quality pieces of irony. When you actually think about it a lot of these characters are great fun too.

You can take Animal House one of two ways. Either it glorifies fraternity life to chaotic proportions or it’s a satirical mockery of the collegiate institutions. Either way, the film works, because the bottom line is that it has laughs. Sure, some of them take hold of nostalgia while simultaneous instigating the trend towards crude, gross-out humor, but Animal House has some generally uproarious moments of mayhem to match some quality pieces of irony. When you actually think about it a lot of these characters are great fun too.

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments.

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments. At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame.

At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame. Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works.

Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works. But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.

But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.

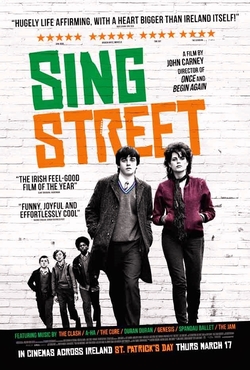

A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.

A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.

I did a double take when I saw an article indicating the passings of the Classic Hollywood musical starlet Gloria DeHaven. She was 91. I could have sworn I just was thinking about her recently and I was. Just last week I came across her in a publicity still with two other young stars who I’ve since forgotten. The three of them were sitting at a table at some gala and they were unfamiliar but in that image DeHaven left an impression on me.

I did a double take when I saw an article indicating the passings of the Classic Hollywood musical starlet Gloria DeHaven. She was 91. I could have sworn I just was thinking about her recently and I was. Just last week I came across her in a publicity still with two other young stars who I’ve since forgotten. The three of them were sitting at a table at some gala and they were unfamiliar but in that image DeHaven left an impression on me.

an anxious Mrs. Carala begins to listlessly comb the streets trying to gather what happened to her lover. Where did he go? Julien

an anxious Mrs. Carala begins to listlessly comb the streets trying to gather what happened to her lover. Where did he go? Julien