“You don’t love me. You just think I’m some kind of animal you trapped.”

Forgive me if you disagree, but Marnie has wrapped around it the full confidence of Alfred Hitchcock with all his trick and thematic ideas. Its use of visuals to cue the action. The intensity of both color and the swirling score of Bernard Hermann (indeed, his final with Hitch), creating this almost obsessive fever dream.

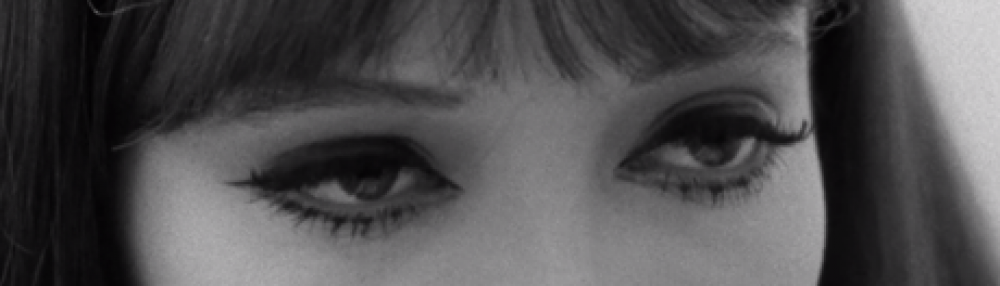

Tippie Hedren returns as an icy, calculated blonde more like Vertigo than The Birds, and it feels like with the talents at his disposal and his harnessing of all the studio system has to offer, he’s able to make it sing like a finely wrought orchestra. While not his best film, it stands proud and tall next to his most identifiable works.

If we are to tinker with the auteur theory, we must also acknowledge cinematographer Robert Burks, who had worked on over a dozen Hitchcock pictures. This would be his last. Then, editor George Tomasini, who had a stellar run with “The Master of Suspense” in his own right, would die in 1964. One could see how you could easily situate Marnie as the end of one of the most fertile periods of filmmaking and also the most terrifying.

These words are chosen purposefully. Because Marnie is not another man on the run thriller or even a game of romantic cat-and-mouse like To Catch a Thief. It fits into the lineage of the Vertigos and Psychos where it feels like Hitchcock is dipping into perturbing territory, partially because it feels self-reflexive, and it deals in the potentially grotesque and unseemly sides of humanity.

Marnie opens on a bag. The back of a woman walking to a train station. We don’t see a face before we cut to a man who bemoans a bank robbery. His secretary ran off with some of his funds.

Eventually, we learn this woman is prone to such behavior. She’s taken many such jobs and undoubtedly committed many such infractions under different aliases. However, her true name is Marnie and like a dutiful daughter, she turns up on her invalid mother’s doorstep to check in on her, give her gifts, and try to earn more of her affection.

Because it becomes immediately apparent this woman has attachment and mother issues; she’s an independent woman yes, who is also independent of men, but she hangs onto her mother’s love. Even covets after it and clings to it jealously when maternal affections are directed towards a neighbor’s little girl. And then, she leaves as quickly as she arrives.

Her cycle begins again when she’s up for a new job at Rutland & Co. The exchange during her interview would be banal if not for a certain undercurrent, the dissonance at the core of the entire picture. They’ve done business with her former employer, but she has no way of knowing that.

The one man who knows her secret is there too. His name is Mark Rutland (Sean Connery). He looks on rather bemusedly as she explains her backstory to her interviewer. Something about a deceased husband and leaving Pittsburgh behind for more demanding, interesting work. As Rutland watches her, it serves a kind of dual-purpose, giving rise to our conflict while also highlighting this kind of queasy sexism in the workplace. Where women are hired as objects and often viewed as such.

He knows and still hires her out of curiosity — is that the case? However, there’s something more — a kind of kleptomania — and Hitchcock funnels the entire movie through Marnie’s private obsessions. So as a secretary drones on about some HR forms, we are busy watching the office manager pull out his key and unlock the safe. We vicariously take on the obsessions of Marnie — caught in the same vortex thanks to Hitchcock’s camera — a camera that enters a fevered frenzy whenever she sees the color red. It’s akin to Jimmy Stewart’s Vertigo in how it totally usurps the picture in an instant.

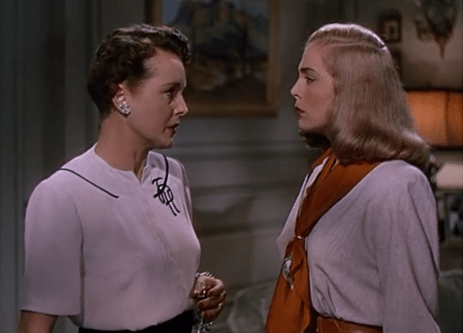

On a very different note, it’s always a pleasure to see Mariette Hartley, a personal favorite in TV reruns, and assuredly in Ride The High Country. But it is Diane Baker who might be the unsung hero of the movie and Hitchcock, if anything, sets her up as an integral figure to cement the film’s core drama. She is Marnie’s foil and ready to protect Mark even as she’s intent on winning him over.

But the relationship between Rutland and Ms. Edgar continues to vacillate, exemplified by very pointed snatches of dialogue. Take for instance, Rutland’s training in Zoological science or as he puts it “instinctual behavior.” He likens predators out on the Sahara to “the criminal class of the animal world,” and he’s as fascinated by Marnie as he is passionate about her.

They go to the races and then to see his father’s stables maintaining these implicit themes of husbandry and animalistic desires raging through Marnie’s core. She cannot help these impulses.

It’s true the film boasts some phenomenal wide shots: The first I’m thinking of is inside the stable before cutting to a close-up to the passionate embrace of our romantic leads. The second is an exercise in irony. Marnie is in the midst of her first burgle of the company safe. She snuck out of a bathroom stall after hours. Just around the partition, the night cleaning lady goes about her duties. To each her own.

For several minutes it is a silent movie. No music. I don’t think Hedren makes a sound. Because of course, Hitchcock is milking the moment only to magnify it seconds later. It reminds us how marvelous he was at punctuating the drama, lest his filmmaking ever be mistaken for realism.

Marnie continues in its duplicity as Rutland first accuses his employee of her theft and then comes right back around with the proposal of marriage. It drudges up the unseemly realities of sexual harassment and powerlessness as Marnie cries out about how she can’t bear to be handled by men. She doesn’t want to get married. It’s degrading. Even animal.

“You say no thanks to one of them and then bingo, you’re a candidate for the funny farm.” It breaks my heart even as I feel implicated in the issues. No, I wasn’t born then, but the indiscretions against women have not totally been expunged at least while men still have lust in their hearts. Hitch is part of the problem. I am part of the problem by any sin of omission or even passivity.

Before there was a mystery plot to hang its hat on in Vertigo or the money propelling Psycho. With Marnie, it hardly feels as if there’s a pretense to the often demented predilections of humanity. Husband and wife are “playing doctor” and free association with Marnie feeling as if she’s continually being needled by her spouse’s callous analysis. Is this love or torture?

We mentioned Diane Baker before and it’s worth acknowledging her again. She is slightly impetuous and a bit impish — ready to go to war for her man. Hitchcock even gives her a line to mirror Norman Bates from Psycho as she offers observation on Marnie (A girl’s best friend is her mother). But she also eavesdrops because it’s this that allows her to know the film’s main secret and look to bring it to the surface.

The next sequence opens with that unmistakable Hitchcock high angle, at the party. It’s Notorious rehashed and yet instead of a key in the hand, it is the front door because through it will come a very important person: Someone who can implicate Marnie and unravel the stasis Mark has willingly corroborated for her. They must find a way to get out of this, to come to a mutual agreement, or else Marnie is sunk.

I must admit, this and the sense of suspense anticipated by the climax, are of the most intriguing since the psychology the final flashback relies upon feels too convenient. Maybe Hitchcock does not really care about any of this. It is a bit like Spellbound, but now it feels even more antiquated, whereas the moments leading up to the reveal of the trauma are contorted and alive, horrifying and convicting all at once.

Others could do it better, but I would be remiss not to mention the storyline of Hedren and Hitchcock, who harassed her all through the shoot. It’s an unsettling reminder of how he would control women and beyond that, how toxic masculinity has fueled our society and industries like Hollywood. It reveals the underlining brokenness in many of us that come out compulsively. It’s almost like we do what we do not want to do or we give ourselves over to them entirely. And what a nightmare that is.

Psychology cannot completely dispel our fears nor does it warrant a society and social spheres where men take advantage of women and where women feel fearful and scandalized. Forget his films. Hitchcock himself is emblematic of problematic fissures in society. That’s a great deal of what makes his film’s so disconcerting.

However, just as he tanked Tippi Hedren’s career, Hitchcock would never quite be the same. Not because of this mind you, unless there was some force of karma working against him I’m unaware of. Instead, the industry was changing and also the structures around him that he had to work with.

Torn Curtain and Topaz are passable films with glimpses of his cinematic eye, but they never amount to the same kind of intoxicating, bewitching drama we would see during his high point during the 1950s and early 60s. Of course, Frenzy was what some called a return to form, but it was, again, back in his native England so it’s obviously laced with a different flavor. His final film was in 1976 — Family Plot — and if it wasn’t evident already the industry had changed.

By then, he was a revered master but more of a relic than an up-and-coming auteur. No, Marnie feels like an inflection point as if it’s catching his very particular genius in a moment in time. It’s also a startling caveat to the career of one of the most lauded directors Hollywood has ever known. We cannot fully speak about one without reflecting on the other.

3.5/5 Stars

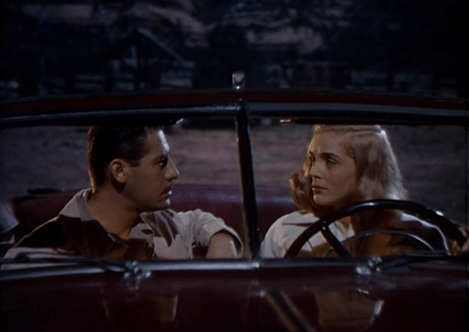

The beauty of a picture like this comes with the efficiency of the drama with a prison breakout occurring under the opening credits. Soon we learn a notorious, shadowy criminal named Kluger has broken out of Folsom prison.

The beauty of a picture like this comes with the efficiency of the drama with a prison breakout occurring under the opening credits. Soon we learn a notorious, shadowy criminal named Kluger has broken out of Folsom prison.