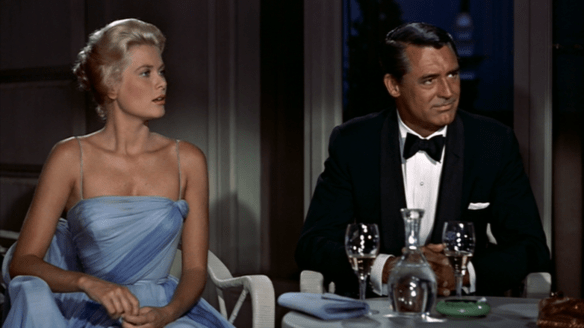

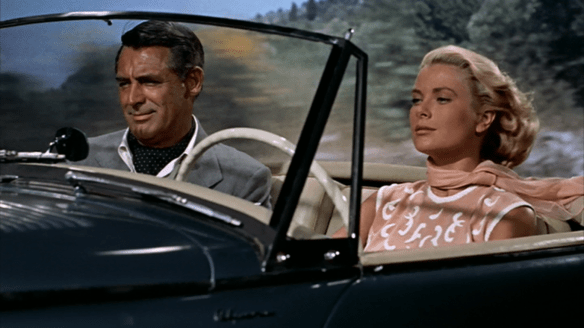

For all intent and purposes, Psycho could be an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Hitchcock knew that better than anyone else. Foregoing the more lavish Technicolor tones he had used in Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959) and lacking the same type of studio backing, he shot this film in the much cheaper black and white format and brought on a great deal of his television crew to make this production a much more inexpensive package.

In that way alone it paled in comparison to some of its much more ostentatious predecessors but that cannot for a moment take away from the impact or cultural clout that Hitchcock still managed — truly topping any of his previous efforts to date. If not his greatest film, then Psycho was certainly his greatest feat of marketing and ingenuity. Because he would never allow his public to forget their experience witnessing Psycho and very few have for generations with it becoming so closely tied to our public consciousness.

The plotline itself is a simple affair of love and small-time crime set in Arizona then transplanted to California. Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) has a man but a life with him seems unlikely especially with both of them being terminally strapped for cash. He’s got alimony to pay and she makes very little on a secretarial salary. But when $40,000 is dropped on her desk in cold hard cash — money she is supposed to deposit in the local bank — in a brief moment of decision she attempts to buy happiness.

She takes the money and keeps on going. From the moment Marion first sees her boss on a crosswalk as she drives off with the money, Bernard Hermann’s score starts pounding. Every time she hits the gas the composer does too and it’s one of the most unnerving pairings in cinematic history.

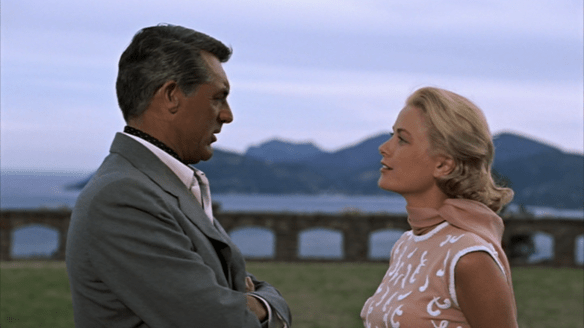

Even without the scoring, this would still be matchless silent storytelling and yet it’s improved upon by the music working with the image. A paranoid Leigh becomes the latest iteration of Hitchcock’s icy blonde, curt and still constantly looking over her shoulder because she is not made to be a lawbreaker. She tries to dodge the interrogation of a suspicious policeman and brushes off the friendly salesmanship of California Charlie (John Anderson). But she rides on no thanks to the guilt written all over her face only to be impeded by Hitchcock’s latest implement, a fateful rainstorm that lays her up at the first motel she can find: The Bates Motel.

In Vertigo and Psycho, you can see how Hitchcock distinctly puts us in the eyes of the main character so we have no choice but to view the world as they do and it’s highly effective in bringing us into the story. Thus, it’s even more jarring when he rips our star and stand-in away from us brutally and forces us to frantically search for another anchoring character.

That brings us to Norman. Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is such a fascinating character because in one sense he’s like a shy little boy. The moment he asks Marion to have dinner with him is brimming with candor and a pitiful awkwardness — like a boy asking a girl out to the prom or something. That sweetness and social ineptitude are at the core of his being. He can’t hide it just as Anthony Perkins playing Bates feels like he is hardly acting at all. It’s just his way.

The Bates home could be a character in itself, a looming beast that hangs over Marion as the domain of the unobserved Mrs. Bates. It poses itself as a portent of Norman’s own ominous instability along with his pointed drawing room conversation with Marion where he freely discloses, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?”

That, of course, brings us to the famed shower scene that is a tour de force not only in editing but in the synthesis of all the cinematic components from the image, to sound, to the scoring of Hermann’s impeccable cacophony of screeching strings. It stands alone as arguably the single most iconic scene in all the movies. Thus, it’s surprising that from the very moment Hitchcock was showing Leigh flush some pieces of paper down a toilet he was already making history — because bathrooms were long-held off-limit locations. Hitchcock made them far worse for folks after Psycho.

He also starts moving around the bathroom in a way that’s vaguely reminiscent of Rear Window’s opening. Finally, cutting from the drain to the eye of Marion Crane suggesting the same spiraling black holes of emptiness as Vertigo. It pretty much sums of the conclusion of her life.

But then we’re back to Norman. There’s an extreme distaste in how goes about cleaning up the bathroom but also a certain industry to it. He gets to it silently and efficiently in another one of Hitchcock’s great sequences that unfold without the aid of any dialogue whatsoever until it leads us the precipice of the swamp where Marion’s car is disposed of.

It’s in these interludes that we understand the full gravity of Hitch’s wicked humor. That money — the load of cash that propelled the film forward — is cast aside as simply as that. No two thoughts about it as if to say you thought that’s what this picture was about but he’s not entirely interested in that. He just wants to hook his audience on that objective before sending them hurtling in completely different directions.

John Galvin plays Leigh’s lover and he’s the stark contrast to Perkins’ character. Both dark-haired and handsome but Sam is a virile man even a masculine ideal of the 50s and 60s. Nevertheless, he joins forces with Lila Crane (Vera Miles) Marion’s concerned sister, subsequently becoming the driving force in the latter stages.

But also of note is the hired private investigator named Arbogast (Martin Balsam) who coincidentally comes onto the scene at the same time at the behest of the old coot that lost $40,000. Balsam a wonderful character actor throughout his career, not surprisingly appeared in two episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and he’s at his best as he questions Norman Bates in that genial manner of his about his person of interest, one Marion Crane.

At this point, in some small way, it feels like we are a bit of an accomplice in this crime of Norman’s. Complicit in his secret and as Arbogast digs around for answers we crawl inside our skin. Norman tries to cover up and we know he’ll be caught in his lie. Hitchcock frames his nervousness most overtly peering over to look at the guest registry knowing that something might give him away.

For its day and age, Psycho goes into admittedly dark and taboo territory. But what’s most unsettling is the subverted ideas of romance it showcases. Marion is looking for some form of companionship. She has desires for the American Dream including money and love. All the things that lifestyle entails and yet her desires are quickly snuffed out never to be realized. She doesn’t even receive the hope of love because on the horizon there is nothing for her — only the nothingness of a drain taking away her lifeblood.

Then, of course, Norman is so closely intertwined with his mother that it destroys his being so much so that he cannot even comprehend how to cope with other people. He’s so injured and wounded by a dominating woman and a lack of love that he has no healthy way to express his love and it’s not so much his undoing as it is his stumbling block. Sure it makes for chilling outcomes and a remarkable turn from Anthony Perkins but what resonates time and time again is the pitiful brokenness within Norman Bates. It’s all there in his famed observation that “A boy’s best friend is his mother.” His is a sorry state of mind.

Even in Sam and Lila, we find our best chance at romantic satisfaction. But that relationship too falls on problems when you cast it in the light of Vertigo. If they do continue their relationship, will it simply be because Sam sees Marion in his sister and wishes to have that or does he see the true worth of this woman in front of him blessed with an insurmountable persistence? If anyone can make it work they can but that is not to say it will not be messy. After all, this is a film of messiness — relationally, psychologically, morally. We all go a little mad sometimes. That’s why we’re not to go through life alone. We’re communal beings.

In the denouement, a psychiatrist tries to explain things away and provide a voice of reason that looks to stabilize everything his audience has just ingested. But even that fails to undo and rationalize Norman Bates completely. Yes, his psychological instabilities, his compartmentalized personalities, and the utter dissonance coursing through him can be understood at least partially by such deductions. Human psychology has its place as does scientific thought. Still, that cannot take away from that final shot as the voice inside Norman’s head keeps talking to us and he raises his eyes with a possessed grin breaking out over his face.

There is no explanation that can be given for that look. It burns into us. Emblazoned on our minds and sending shivers down the spine. That image and all those proceeding are what the cinema is capable of, evoking emotion far beyond what any word can possibly begin to unearth. That is the exorbitantly visceral brilliance of Psycho. Hitchcock was a proponent of so-called pure cinema and this is yet another showing of the “Master of Suspense” at the peak of his creative powers. Few filmmakers have made such a stream of classics of such variety and of such a multitude in such a condensed span of time — each one slowly reworking and ultimately rewriting the rules of suspense. Psycho is yet another testament to that.

5/5 Stars

Though director Anthony Mann later made a name for himself with a string of Westerns pairing him with James Stewart, it’s just as easy to enjoy him for some of the diverting crime pictures he helped craft. Everything from Raw Deal (1948) to T-Men (1947), He Walked by Night (1948), and of course this little number.

Though director Anthony Mann later made a name for himself with a string of Westerns pairing him with James Stewart, it’s just as easy to enjoy him for some of the diverting crime pictures he helped craft. Everything from Raw Deal (1948) to T-Men (1947), He Walked by Night (1948), and of course this little number.

At first glance, this doesn’t seem like the type of picture suited for Steve McQueen and Natalie Wood. He was “The King of Cool.” She was a major player from childhood in numerous classics. Neither was what most people considered a serious actor. They were movie stars. They had charisma and general appeal to the viewing public.

At first glance, this doesn’t seem like the type of picture suited for Steve McQueen and Natalie Wood. He was “The King of Cool.” She was a major player from childhood in numerous classics. Neither was what most people considered a serious actor. They were movie stars. They had charisma and general appeal to the viewing public.

We are met with the scourge of Hitler overrunning mainland Europe. It’s about that time. American isn’t involved in the war. Britain’s getting bombed to smithereens and the rest of Europe is tumbling like rows and rows of tin soldiers.

We are met with the scourge of Hitler overrunning mainland Europe. It’s about that time. American isn’t involved in the war. Britain’s getting bombed to smithereens and the rest of Europe is tumbling like rows and rows of tin soldiers.