The initial inclination for seeing Arnaud Desplechin’s sprawling family drama was the presence of the estimable Catherine Deneuve. And she’s truly wonderful giving a shining, nuanced performance that makes the audience respect her, sympathize with her, and even dislike her a little bit. But the same goes for her entire family. The best word to describe them is messy. Dysfunctional is too sterile. Messy fits what they are. If you think your family is bad around the holidays, the Vuillards have a lot of their own issues to cull through.

The initial inclination for seeing Arnaud Desplechin’s sprawling family drama was the presence of the estimable Catherine Deneuve. And she’s truly wonderful giving a shining, nuanced performance that makes the audience respect her, sympathize with her, and even dislike her a little bit. But the same goes for her entire family. The best word to describe them is messy. Dysfunctional is too sterile. Messy fits what they are. If you think your family is bad around the holidays, the Vuillards have a lot of their own issues to cull through.

The inciting incident sends a shock wave through their already crumbling family unit. Their matriarch has been diagnosed with bone marrow cancer and must make the difficult decision of whether or not to risk treatment or go without. But Deneuve carries herself with that same quietly assured beauty that she’s had even since the days of Umbrellas of Cherbourg. In this capacity, she makes A Christmas Tale, far from a tearful, sobfest. She’s strong, distant, and you might even venture to say fearless.

And because of her strength, this story is not only about her own plight – it’s easy to downplay it because she is so resilient – but it frames the rest of the interconnecting relationships. It began when her first son passed away. The children who followed included Elizabeth (Anne Cosigny) who became the oldest and grew up to be a successful playwright. Junon’s middle child Henri (Mathieu Amalric) can best be described as the black sheep while the youngest, Ivan, was caught in the midst of the familial turmoil.

Because the issues go back at least five years before Junon gets her life-altering news. It was five years ago that Elizabeth paid Henri’s way out of an extended prison sentence (for a reason that is never explained) with the stipulation that she never has to see her brother again. Not at family gatherings, not for anything. And she gets her way for a time.

But with Junon’s news she and her husband Abel (Jean-Paul Roussillon) realize this is a crucial time to get their family back together because, above all, their matriarch needs a donor and due to her unique genetic makeup, a family member is her best bet.

Underlying these overt issues are numerous tensions that go beyond sibling grudges and sickness. Elizabeth’s own relationships have been fraught with unhappiness and her son Paul has been struggling through a bout of depression. Ivan and his wife (Chiarra Mastroianni) are seemingly happy with two young boys of her own. But old secrets about unrequited love get dredged up and Sylvia is looking for answers of her own. Although it’s a side note, it’s striking that Chiarra Mastroianni is Deneuve’s real-life daughter and in her eyes, I see the spitting image of her father, the icon, Marcello Mastroianni.

There’s also a lot of truth and honesty buried within A Christma Tale and in most competitions, it would win for the most melancholy of yuletide offerings. However, it’s important to note that its darkness is balanced out with romance, comedy, and a decent dose of apathy as well.

Still, the most troubling thing about A Christmas Tale is not the fact that it is extremely transparent, but the reality that the themes of Christmas have no bearing on its plot. We leave these characters different than they were before but whether they are better for it is up for debate.

The sentimentality of a It’s Wonderful Life crescendo would be overdone and fake in this context but some sort of reevaluation still seems necessary. Because without faith in anything — faith in their family is ludicrous — their world looks utterly hopeless. The two little grandsons wait in front of the nativity staying up to get a glimpse at Jesus (perhaps mistaken for Santa Claus) and their father calmly states they should go to bed because he’s never existed anyways. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with holding such beliefs.

Even the fact that Junon and her grown son Henri attend midnight mass is an interesting development. But during this season emblematic of hope and joy, it seems like the Vuillard’s can have very little of either one. Henri can be his mother’s savior for a time by extending her life for 1.7 years or whatever the probabilities suggest. But then what?

It’s this reason and not the family drama that ultimately makes A Christmas Tale a downer holiday story. Its denouement feels rather like a dead end more than fresh beginnings. Because Nietzche and coin flips are not the most satisfying ways to decipher the incomprehensibility of life – especially with death looming large during the holidays.

But that’s only one man’s opinion. That’s not to downplay all that is candid about this film in any way. If you are intrigued by the interpersonal relationships and entanglements of a family — may be a lot like yours and mine — this film is an elightening exposé.

3.5/5 Stars

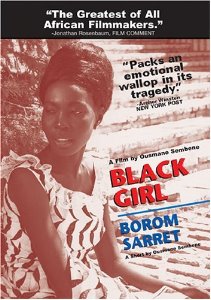

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once.

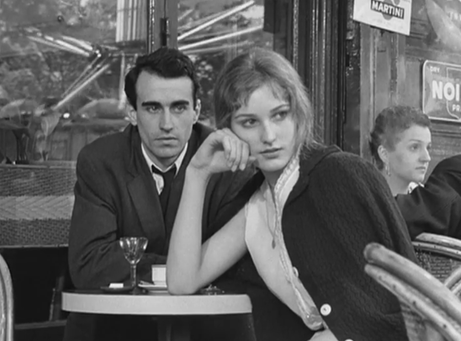

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once. There might be an initial predilection to call The Soft Skin Francois Truffaut’s most conventional film to date, but for me, it shows at this fairly early point in his career he seems to have grasped the main tenets of traditional filmmaking. Because his first films are full of life, energy, and idiosyncratic verve that easily charm their audience but here we see a film that in most ways looks like other classic works, well constructed and still quite engaging. Because within this very framework Truffaut is able to play around with issues that in themselves are still quite compelling. Love, intimacy, infidelity, and the like. Even with familiar names like Truffaut and Raoul Coutard, it feels very un-Nouvelle Vague. And that’s okay.

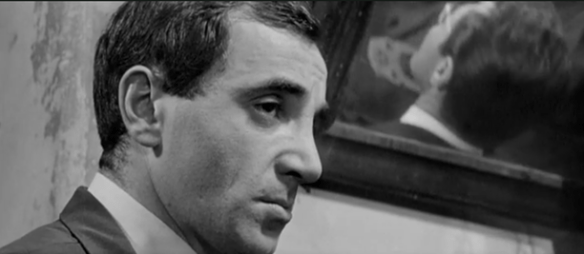

There might be an initial predilection to call The Soft Skin Francois Truffaut’s most conventional film to date, but for me, it shows at this fairly early point in his career he seems to have grasped the main tenets of traditional filmmaking. Because his first films are full of life, energy, and idiosyncratic verve that easily charm their audience but here we see a film that in most ways looks like other classic works, well constructed and still quite engaging. Because within this very framework Truffaut is able to play around with issues that in themselves are still quite compelling. Love, intimacy, infidelity, and the like. Even with familiar names like Truffaut and Raoul Coutard, it feels very un-Nouvelle Vague. And that’s okay. Pickpocket is an intricately staged, truly intimate character study from the inimitable Robert Bresson solidifying itself as one of his greatest works. As was his practice, Bresson took Martin LaSalle, a non-actor to be his leading protagonist.

Pickpocket is an intricately staged, truly intimate character study from the inimitable Robert Bresson solidifying itself as one of his greatest works. As was his practice, Bresson took Martin LaSalle, a non-actor to be his leading protagonist.

The opening credits of Vivre sa Vie commence with the opening note “dedicated to B-movies” and indeed many of Jean-Luc Godard’s best films could make the same claim. They’re smalltime stories about little people living rather pathetic lives if you wish to be brutally honest. This isn’t Hollywood.

The opening credits of Vivre sa Vie commence with the opening note “dedicated to B-movies” and indeed many of Jean-Luc Godard’s best films could make the same claim. They’re smalltime stories about little people living rather pathetic lives if you wish to be brutally honest. This isn’t Hollywood. It’s a joy to watch Agnes Varda dance. Or, more precisely, it’s a joy to watch her camera dance. Because that’s exactly what it does. Her film opens in color, catching our attention, vibrant and alive as the credits roll and a young woman (Corinne Marchand) gets her fortune read by an old lady. She’s worried about her fate. We can gather that much and this is her way of coping. Superstition and tarot cards but she’s trying and the results are not quite to her fancy.

It’s a joy to watch Agnes Varda dance. Or, more precisely, it’s a joy to watch her camera dance. Because that’s exactly what it does. Her film opens in color, catching our attention, vibrant and alive as the credits roll and a young woman (Corinne Marchand) gets her fortune read by an old lady. She’s worried about her fate. We can gather that much and this is her way of coping. Superstition and tarot cards but she’s trying and the results are not quite to her fancy. There’s something overwhelmingly soothing about Ozu, simultaneously slowing my pulse and calming my nerves. Yes, An Autumn Afternoon stands as his final film. Yes, he would sadly pass away the following year. But there’s a comfort to watching his films unfold — even his last one. The drama is everyday and somehow disarming and pleasant. We often take for granted that Ozu was not planning to end here. This was not supposed to be his last film. It just happened that way.

There’s something overwhelmingly soothing about Ozu, simultaneously slowing my pulse and calming my nerves. Yes, An Autumn Afternoon stands as his final film. Yes, he would sadly pass away the following year. But there’s a comfort to watching his films unfold — even his last one. The drama is everyday and somehow disarming and pleasant. We often take for granted that Ozu was not planning to end here. This was not supposed to be his last film. It just happened that way. Sophie Scholl: The Final Days is a film that people need to see or at the very least people need to know the story being told. For those who don’t know, Sophie Scholl was a twenty-something college student. That’s not altogether extraordinary. But her circumstances and what she did in the midst of them were remarkable.

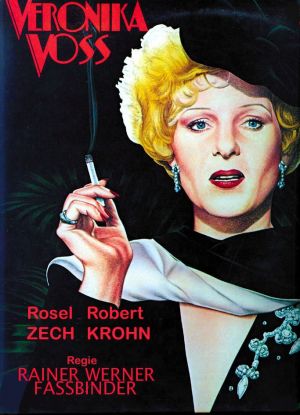

Sophie Scholl: The Final Days is a film that people need to see or at the very least people need to know the story being told. For those who don’t know, Sophie Scholl was a twenty-something college student. That’s not altogether extraordinary. But her circumstances and what she did in the midst of them were remarkable. You get a sense that if they had ever met, Norma Desmond and Veronika Voss might have been good friends. Either that or they would have hated each other’s guts. And the reason for that is quite clear. They share so many similarities. Both are fading stars, prima donnas, who used to be big shots and now not so much and that seems to scare them so much so that they try and cover their insecurities with delusions of grandeur. Having to look at your near reflection would be utterly unnerving.

You get a sense that if they had ever met, Norma Desmond and Veronika Voss might have been good friends. Either that or they would have hated each other’s guts. And the reason for that is quite clear. They share so many similarities. Both are fading stars, prima donnas, who used to be big shots and now not so much and that seems to scare them so much so that they try and cover their insecurities with delusions of grandeur. Having to look at your near reflection would be utterly unnerving.