“Surely I can be a good son and a good husband.”

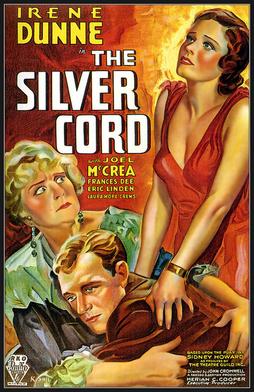

Whether it means to or not, the opening interlude of The Silver Cord plays like a comic inversion of typical Hollywood. It opens in Heidelberg, and they make us blink; they’re actually speaking German and Irene Dunne is one of them!

Then Joel McCrea wanders in, Dunne at the microscope deep in her work. He kisses her on the nape of the neck, and she responds coolly in English. I got the same sudden delight out of this moment that I did in the train car at the start of Design for Living. Why? For a brief instance, it caught me off guard and I smiled.

The rest of The Silver Cord begins as nice as you please like a hunky-dory sunbeam. She is a world-class biologist. He is an up-and-coming architect. New jobs beckon in New York, marital bliss swells around them, and meeting the brother and his new wife gets off to a grand start. It’s only the mother who remains to be seen.

It just so happens Mrs. Phelps (Laura Hope Crewes reprising her stellar stage role) is the lynchpin. She’s a maternal hurricane of frenzied energy, shouting her son’s name elatedly in the drawing-room, and obsessed with him a bit more than what feels kosher. She also meets her new daughter-in-law even as the ripples of slight agitation show themselves in how she subtlety rebuffs her younger son’s fiancée. There’s already tension.

In fact, she dominates the entire household with her ways, whether it’s her views on parenting or how she conveniently puts Dave in his old room so he’s separated from his wife. It becomes plainly apparent she a smothering woman; It feels like she’s playing a desperate game of tug-of-war as she lauds an old-fashioned conception of motherhood while coveting a piece of her son’s heart.

In another moment, Mrs. Phelps literally tucks her grown son into bed. But there’s an ulterior motive. She wants all the dirt on his new wife and then she proceeds to natter on about how possessive, exacting, and selfish she is. “If only she learned to care for me as I care for her,” she says. The irony of her words fails to leave an imprint on those actually involved in the conversation. Of course, a moment later finds the belittled wife awkwardly walking in on mother and son. Yet another disconcerting scenario.

We have a two-front war on our hands. The fight is first over Robert (Eric Linden) and then David (McCrea). First, dear old Mom talks her impressionable younger son out of his love for his wife, Hester (Frances Dee), going so far as to poison his mind so her undue influence is felt in full force even when she’s not in the frame. After all, she is an insinuating, controlling woman who plays mind games and whether she does them subconsciously or not, it doesn’t much matter. She’s a genuine terror.

Crewes is so infuriating in her effectiveness making it so difficult to be civil and to concede without falling over backward like a bowling pin. If we learn anything about Christina (Dunne), it’s the fact she has a life and aspirations to go with them. A husband is part of it but as things unravel, she’s going to stand up for herself. One thing’s for certain. It moves fast.

Soon Christina makes a plea to her husband to relinquish the arid places in his heart where he retires. She plays another card by supplying a grand surprise of her own. Mrs. Phelps home is a swath of his heart on a larger scale — one she is looking to hold onto as her own by any means possible, but Christina makes it clear she will not go down without a fight.

Meanwhile, Hester, who has been subjected to the torment the longest, is about ready to burst. They have “shocking” conversations about something as controversial as babies, and she’s just about had it. She can’t take how her marriage and her own aspirations for children have been twisted and trampled into something bad.

She’s left a trembling hysterical mess driven to get out of the house. And she cannot be anything if not a portent for what might happen to Christina as well if she doesn’t take her own leave.

Because among Mother’s many attributes is also diabolical hypochondria. The jaundice doctor rightly acknowledges a stick of dynamite would be needed to subdue her. In fact, she peps right up just when things come back around to what she’s always envisioned for her sons with wives out of the way.

If you’ll afford me a brief tangent, even with Irene Dunne wedged between them in the frame, it’s hard not to look at France Dee and Joel McCrea and think of what a fine couple they would make. What’s even more remarkable is how long they made a couple: 57 years!

Although the story’s internal logic is purposefully maddening, it gives way to a fine bit of melodrama because it manipulates the scenario in such a way to make us feel almost immediate revulsion, and it builds for little over an hour in fairly splendid fashion.

A standout moment comes with Irene Dunne ably stripping her mother-in-law down to size with a perceptive deconstruction of all her various hangups and maternal misdemeanors. She puts words to all the many things we take issue with but are unable to say as passive observers.

Her is a woman finding romance in motherhood where she didn’t find it in marriage, highlighting the peculiar dynamics the movie is being drawn up on. Mrs. Phelps reaches her own point of hysteria though she’s too delusional — too set up in her own ways — to understand who she is and what she’s doing. Still, if you can bear it, The Silver Cord is an effective drama for all it manages to heap on top of us.

3.5/5 Stars

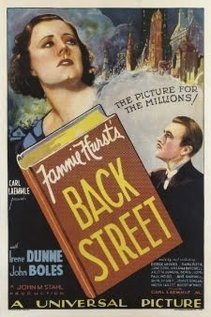

“There’s not one woman in a million who has ever found happiness in the back streets of any man’s life.”

“There’s not one woman in a million who has ever found happiness in the back streets of any man’s life.”