“I guess you don’t have to be colored to be unhappy.”

“No, but it sure helps.”

These lines come near the end of Take a Giant Step. The adolescent maelstrom of the movie has subsided and Spence Scott has found a newfound connection with his Pop (Frederick O’Neal). It could be the final moral in a sitcom episode: all teenagers have problems. They’re all disillusioned and unhappy. And yet rather wryly, Mr. Scott subverts the lesson in what feels like an emblematic moment. It’s not a grandstanding watershed, but it speaks to the black experience like few films of the era.

I love Johnny Nash to death, but there are times as he goes through the paces of his performance in Take a Giant Step when he doesn’t seem ready to carry the weight of this movie. He’s constantly stomping around angry at the world and lashing out at everyone. It doesn’t matter who it is. There are moments of sympathy, but most of it is boyish vitriol.

However, the movie itself brings together so many compelling ideas, and to have them out in the public forum in 1959 feels like such a groundbreaking feat. In this regard, it predates A Raisin in The Sun, which has become a bit of the historical standard-bearer.

Here in Louis S. Peterson’s story, adapted from his own groundbreaking stage play, a black high schooler in a predominantly white community feels the anxiety of never fitting in, having “friends” keep their distance, and parents who ride him when he gets home.

It’s teenage angst to its zenith, and then we realize this environment could not be structured better to alienate Spence if it tried. The inciting moment is when his white history teacher recounts the narrative of the Civil War where dumb and helpless blacks had to be saved by Northern benefactors. There’s no mention of Frederick Douglass, willful insurrections, or any counter-narratives.

What makes it worse is the boy’s isolation. No one can understand where he’s coming from even if they wanted to. He is alone in this fight and in his experience. What a helpless and debilitating position to be in. A one-man rebellion is a hard fight to win and in the end, his teenage insurrection gets him expelled from school. Only he knows what that will mean when his parents find out.

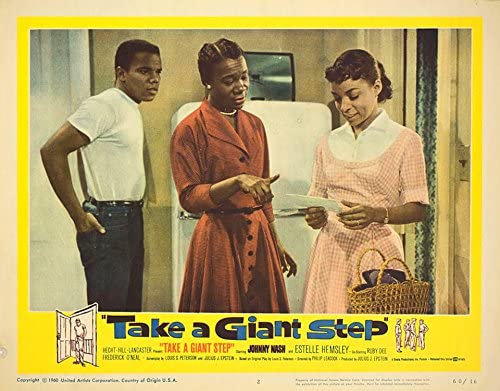

While I can’t say Nash is the best actor, he’s surrounded by some luminary talents who elevate this story and make the relationships mean something. I’m speaking, in particular, about the great Estelle Helmsley — boy, do I love her after this film — and then Ruby Dee, who shines in her own right.

Helmsley, a famed stage player takes up her post as the invalid grandmother who spends most of her days incapacitated upstairs. But if her body is weak, then her spirit is more than willing, playing first sparring partner and then confidante for her sharp-tongued grandson. Somehow she has a privileged position, seeing his predicament as his parents never can, and she acts accordingly providing a kind of psychological refuge.

Dee, on her part, plays the family’s cordial housekeeper Christine always affectionately teasing Spence, and then becoming another friend to the friendless. Although black performers were often subjugated to these kinds of domestic roles, Dee is still allowed the agency to speak volumes.

Not only does it say something about her character, it provides commentary on the Scott family that they are able to keep “help.” Likewise, she’s capable of tough love, but also feels inherently inviting. Spence’s disillusionment and raging hormones make Christine an obvious object of affection.

Perhaps because Spence exists in a world where so few people understand him, these two women leave such a stirring impression because somehow they actually get through to him. They receive his ire and turn right around and help him grow up, by simultaneously extending compassion.

In some ways, watching Take a Giant Step reminded me of No Down Payment, another post-war film that takes the white middle-class American dream and puts it up to scrutiny. It’s easy to whitewash the fences and construct sitcoms that either overtly or implicitly construct visions of what the world is supposed to look like.

These two films, in particular, show the fissures that seep into the idealistic depictions of suburbia when there are outsiders who don’t conform to the accepted status quo. The irony is how they try and fit into the prevailing norms and are still rarely granted access.

Rather like the ignorant history teacher, Hollywood rarely gives us such showcases, but every once in a while we get a story that runs against the grain to suggest other points of view, whether they belong to Blacks or Japanese-Americans. Despite any overt imperfections, I’m supremely grateful that we have these films. More people should see them and wrestle with what they have to offer.

3/5 Stars