Robert Siodmak might not be the foremost of lauded directors, but it’s indisputable that film noir as a genre, a movement, a style, whatever you want to call it, would be a lot less interesting without him.

Robert Siodmak might not be the foremost of lauded directors, but it’s indisputable that film noir as a genre, a movement, a style, whatever you want to call it, would be a lot less interesting without him.

Phantom Lady is a perfect illustration of that fact as it takes a simple plotting device and rides it through the entire story to a fitting conclusion. It’s not a taut thriller or really anything of the kind but the characters and even the cinematic choices make it a surprisingly shadowy delight.

As the title suggests, any explanation of the narrative must begin and end with this phantom lady who, if you want to use storytelling terms, is the MacGuffin, the entity driving the plot forward to its final end. She’s necessary but as we might predict she’s at the same time integral to the story and not at all important.

Because the fact that she is missing is simply a pretense that leads to a response from our hero. And at first, our hero seems pretty obvious, the handsome down on his luck Joe with a pencil mustache (Alan Curtis). Once upon a time, I confused him with another noir regular Brian Dunlevy but no more. Anyways, our actual hero comes to the fore after the inciting incident. This man Scott Henderson all of a sudden comes back from a crummy night at the theater to find himself accused of strangling his wife. The cops seem to have a guilty until proven innocent modus operandi. True, the eyewitnesses for his alibi seem knee deep and yet everyone has hushed up, including a bartender, a jazz drummer, a flamboyant performer. Worst of all his female companion for the evening has vanished into thin air.

With no alibi, Scott still sticks to his ridiculous story that no one believes and he winds up sentenced for the murder of his wife. If you’re still following, it’s at this juncture where the story really begins. Henderson’s plucky secretary “Kansas” (Ella Raines) is smitten with her boss and determined to prove his innocence. So she becomes our intrepid noir hero digging around in the sleazy bars and dance halls, tracking down possible leads. A tight-lipped bartender is subjected to her merciless tailing and she even ingratiates herself to a swinging jazz drummer (Elisha Cook Jr.) who can really make his sticks fly.

They get her closer to the trail but each one becomes a successive dead end. She gains some encouraging allies in the initially skeptical detective Burgess (Thomas Gomez) as well as Scott’s best friend who has just returned from a trip to South America (Franchot Tone). Together they try and wrap up the loose ends. Of course, as an audience, the dramatic irony sets up the tension as we know what’s going on behind the scenes. So this is still partially a mystery as the search for the phantom lady continues but the joke’s really on us because soon enough we know what’s happening. However, whether it’s too late for our heroes is quite another question altogether.

Siodmak does well to develop a stylized atmosphere and there are some especially intriguing touches. The foremost is how many sequences, including the tailing sequence, function without music and yet jazz is utilized in a frenzied interlude that is almost unheard of in noir for its sheer vivacity. It’s oddly disconcerting, the juxtaposition suggesting this utter contrast between personified joy and the darkness that is seeping into the story. After all, a man is about to be sentenced to death. Jazz certainly does not fit the mood.

There’s also the paradigm of the noir working girl played perhaps most iconically by the audacious Ella Raines. In many ways, this is her film and she’s as good and almost better than many a gumshoe and insurance investigators. It’s a role that Raines embodies with great resolve and a certain amount of drive that we can appreciate in a female character of that day and age. She’s far from an objectified figure because she has brains and desires of our own — even if they are all for the well-being of a man.

It also should be noted that this was the first production credit for pioneering British screenwriter Joan Harrison. She was only one of only three woman producers in Hollywood at the time and this is a film that she could certainly be proud of with an impressive noir heroine.

3.5/5 Stars

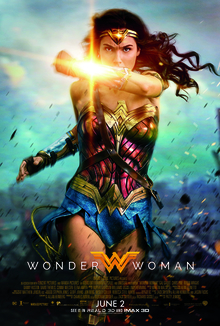

It might sound like meager praise but Wonder Woman is the most engrossing DC offering thus far. It also seems almost unfair to compare across the aisle against main rival Marvel with its terribly lucrative cottage industry or for the very fact that any comparison might suggest how derivative this feature must be.

It might sound like meager praise but Wonder Woman is the most engrossing DC offering thus far. It also seems almost unfair to compare across the aisle against main rival Marvel with its terribly lucrative cottage industry or for the very fact that any comparison might suggest how derivative this feature must be. The strands of our lives are woven together and neither time nor the world can break them.

The strands of our lives are woven together and neither time nor the world can break them. But it’s a chance encounter with a young girl named Jennie (Jennifer Jones) that gives Eben the type of inspiration that every artist dreams of because it’s precisely this spontaneous spark of joyous energy he needs to add something vibrant to his own life. In her constantly evolving role, Jennifer Jones exudes an effervescence, a certain radiance in body and spirit that lights up the screen in embodying this apparition of a girl.

But it’s a chance encounter with a young girl named Jennie (Jennifer Jones) that gives Eben the type of inspiration that every artist dreams of because it’s precisely this spontaneous spark of joyous energy he needs to add something vibrant to his own life. In her constantly evolving role, Jennifer Jones exudes an effervescence, a certain radiance in body and spirit that lights up the screen in embodying this apparition of a girl. I find that despite his pedigree Joseph Cotten still comes off as an underrated actor and with each film I see him, I enjoy him immensely. Maybe for those very qualities. He’s not altogether handsome but he has a pleasant face. His voice isn’t the most formidable or debonair but it does have character. The supporting players lend some Irish flair to the cast and it’s striking that everyone from Ethel Barrymore to Lilian Gish glows with a certain hope. There is no obvious antagonistic force in this film. Eben Adams found his inspiration — the muse of a lifetime — and that passion is enough to lay the foundations of a film.

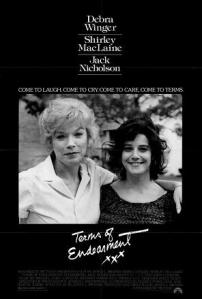

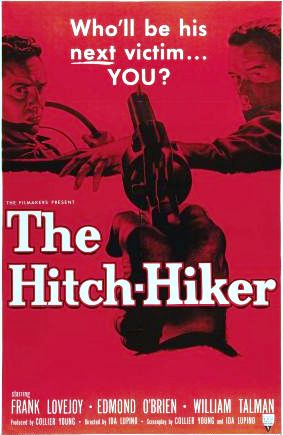

I find that despite his pedigree Joseph Cotten still comes off as an underrated actor and with each film I see him, I enjoy him immensely. Maybe for those very qualities. He’s not altogether handsome but he has a pleasant face. His voice isn’t the most formidable or debonair but it does have character. The supporting players lend some Irish flair to the cast and it’s striking that everyone from Ethel Barrymore to Lilian Gish glows with a certain hope. There is no obvious antagonistic force in this film. Eben Adams found his inspiration — the muse of a lifetime — and that passion is enough to lay the foundations of a film. Part of the harrowing allure of the Hitch-Hiker is that it’s actually based on a true incident that occurred only a year before the events shown. It’s not as if someone took artistic license with some murderers and made it into a horror spectacle. Hitchcock’s Psycho especially comes to mind.

Part of the harrowing allure of the Hitch-Hiker is that it’s actually based on a true incident that occurred only a year before the events shown. It’s not as if someone took artistic license with some murderers and made it into a horror spectacle. Hitchcock’s Psycho especially comes to mind. It disappoints me that I was not more taken with the material than I was but despite not being wholly engaged, there are still some fascinating aspects to Panic in the Streets. Though a somewhat simple picture, it seems possible that I might just need to give it a second viewing soon. Let’s begin with the reality.

It disappoints me that I was not more taken with the material than I was but despite not being wholly engaged, there are still some fascinating aspects to Panic in the Streets. Though a somewhat simple picture, it seems possible that I might just need to give it a second viewing soon. Let’s begin with the reality.

Are you a mod or a rocker? ~ reporter

Are you a mod or a rocker? ~ reporter

I despise you and I pity you. ~ Edmund Gwenn as Mr. Jordan

I despise you and I pity you. ~ Edmund Gwenn as Mr. Jordan Except at first what Harry does, does not seem like infidelity. In one integral scene Harry takes one of those bus tours to see the stars because, after all, Beverly Hills is that land of movie stars and their extravagant lifestyles. Jimmy Stewart, Jack Benny, Oscar Levant, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jane Wyman are all given a nod. There are even a few playful in-jokes to the always genial Edmund Gwenn who turns up as the adoption agent. All of this is essentially fluff but it’s on that same ride where he meets someone — a woman named Phyllis Martin (Ida Lupino).

Except at first what Harry does, does not seem like infidelity. In one integral scene Harry takes one of those bus tours to see the stars because, after all, Beverly Hills is that land of movie stars and their extravagant lifestyles. Jimmy Stewart, Jack Benny, Oscar Levant, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jane Wyman are all given a nod. There are even a few playful in-jokes to the always genial Edmund Gwenn who turns up as the adoption agent. All of this is essentially fluff but it’s on that same ride where he meets someone — a woman named Phyllis Martin (Ida Lupino). It strikes me how it’s often the small, tiny, unassuming pictures that impact me the most and this film did wrench my heart over the course of only a very few minutes. The final court sequence sums up the reasons quite well because it ends the film on a moral note setting up a rather convicting paradigm.

It strikes me how it’s often the small, tiny, unassuming pictures that impact me the most and this film did wrench my heart over the course of only a very few minutes. The final court sequence sums up the reasons quite well because it ends the film on a moral note setting up a rather convicting paradigm.