“Ringo don’t look so tough to me.”

“Ringo don’t look so tough to me.”

Those are the words that propagate a legend and simultaneously follow notorious gunman Jimmy Ringo wherever he goes. There’s always some impetuous kid looking to have it out with him and every time it’s the same result. The kid never listens and Ringo rides off to the next town, wearier than he was the last time.

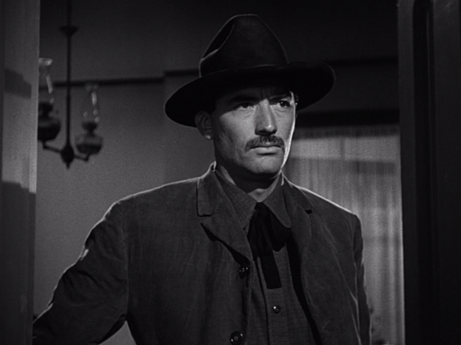

The Gunfighter has a surprisingly vibrant script with numerous names attached to it at different times including William Bowers, Nunnally Johnson, and Andre de Toth. It evolves into a sort of chamber piece made into a carnival show when Jimmy Ringo (Gregory Peck) comes to the town of Cayenne.Kids milling about peering in and catcalling as this “murderer” sits in the saloon like a sideshow attraction.

It’s an oddly compelling commentary on celebrity, and in this case, notoriety as everyone far and wide knows the name Jimmy Ringo and is either in awe of it or ready to prove they’ve got the guts to take him down. He’s constantly being sized up, continually being gawked at, or gossipped about. That’s the price of such fame.

But on the opposite side of the coin, and incidentally, the side no one much cares to think about, there’s a jaded man who’s made a life out of gunning down other men and moving from one town to the next to the next. There’s something very human about growing old and that’s what Jimmy Ringo has done. Because as the years march ever onward your whole mindset shifts along with your priorities. A life on the run doesn’t have the same luster. You want to be able to settle down, to be happy, to be at peace. But old vendettas take a long time to die, continuing just as long as the legends that they follow.

Of all men to understand Ringo, you would think that the local Marshall (Millard Mitchell) would be the last, but he happens to be an old friend of the gunman. They used to run in the same circles before Mark softened up. His life mellowed out, while Ringo’s reputation continued to build.

Of all men to understand Ringo, you would think that the local Marshall (Millard Mitchell) would be the last, but he happens to be an old friend of the gunman. They used to run in the same circles before Mark softened up. His life mellowed out, while Ringo’s reputation continued to build.

The subsequent sequence in the jailhouse illustrates just how much weight a simple name can carry. When the well-to-do ladies of the town come to the sheriff with their petition for justice, they think little of the stranger who tries to shed a little light on Ringo’s point of view. However, the moment they hear his name uttered, everyone is in a tizzy, rushing out of the jail lickety-split. It reflects just how hypocritical their form of morality is.

The main reason Ringo stays in a town that doesn’t want him is all because of a girl (Helen Westcott). He waits and waits, biding his time, for any word from her, and finally, it comes. He gets his wish to see her and his son in private. These scenes behind closed doors are surprisingly intimate, casting the old gunman in an utterly different light.

The main reason Ringo stays in a town that doesn’t want him is all because of a girl (Helen Westcott). He waits and waits, biding his time, for any word from her, and finally, it comes. He gets his wish to see her and his son in private. These scenes behind closed doors are surprisingly intimate, casting the old gunman in an utterly different light.

Of course, none of that saves him when he walks out that door back into the limelight, living the life of Jimmy Ringo, whether he likes it or not. If the three vengeful brothers don’t get him, there’s someone waiting for him up in a second story window or hiding behind a corner. A man like that can never win in the end.

It struck me that this film has some thematic similarities to another film of the same year, All About Eve. Aside from the fact that I personally enjoy Gregory Peck a great deal more than Bette Davis, both films focus on aging icons. While Ringo is not so much manipulated as undermined by his own legacy, his story ends with a young man much like himself riding off into the distance, to take up the life that Ringo led for so long. The specters of such notoriety will haunt the boy until the day he dies, and much like Eve, the deadly cycle begins again. Henry King made an unprecedented 6 films with Peck and this is probably the hallmark for both of them, certainly their most prolific western respectively.

4.5/5 Stars

Saying that Phil Karlson has a penchant for gritty crime dramas is a gross understatement. And yet here again is one of those real tough-guy numbers he was known for, where all you have to do is follow the trail of cigarette smoke and every punch is palpable–coming right off the screen and practically walloping you across the face.

Saying that Phil Karlson has a penchant for gritty crime dramas is a gross understatement. And yet here again is one of those real tough-guy numbers he was known for, where all you have to do is follow the trail of cigarette smoke and every punch is palpable–coming right off the screen and practically walloping you across the face. “Things are only as meaningful as the meaning that we allow them to have.” ~ Beverly

“Things are only as meaningful as the meaning that we allow them to have.” ~ Beverly The fact that Miracle on 34th Street and this film came out the same year seems to suggest that there was something special in the air of New York City that year. It was a magical place, specifically during the Christmas season with Santa Claus going on trial and winning, while tramps helped reform millionaires. Admittedly, It Happened on Fifth Avenue is one of those films that could easily come under fire for its implausible plot, its unabashed sentiment, and any number of other things.

The fact that Miracle on 34th Street and this film came out the same year seems to suggest that there was something special in the air of New York City that year. It was a magical place, specifically during the Christmas season with Santa Claus going on trial and winning, while tramps helped reform millionaires. Admittedly, It Happened on Fifth Avenue is one of those films that could easily come under fire for its implausible plot, its unabashed sentiment, and any number of other things.

Rainbows, the soft misting of waterfalls, and honeymooning couples going through the tunnel of love. It hardly feels threatening at all, but that’s what makes film-noir so delicious. As the film style most reflective of the human condition, it proves that the dark proclivities and jealousies of the human heart can crop of anywhere–even a gorgeous tourist trap like Niagara Falls.

Rainbows, the soft misting of waterfalls, and honeymooning couples going through the tunnel of love. It hardly feels threatening at all, but that’s what makes film-noir so delicious. As the film style most reflective of the human condition, it proves that the dark proclivities and jealousies of the human heart can crop of anywhere–even a gorgeous tourist trap like Niagara Falls. Without a question, Jean Peters becomes our favorite character as Polly, and it was an eye-opening for me personally to see her in a role so vastly different than Pickup on South Street. I had pigeon-holed her, rather erroneously as such a character, but Niagara shows a more tempered side to her persona that felt more representative of her as an actress. Max Showalter plays her husband, the genial and oblivious Ray Cutler, who takes his lovely wife on a long overdue honeymoon, only to have it totally ravaged thanks to the Loomises.

Without a question, Jean Peters becomes our favorite character as Polly, and it was an eye-opening for me personally to see her in a role so vastly different than Pickup on South Street. I had pigeon-holed her, rather erroneously as such a character, but Niagara shows a more tempered side to her persona that felt more representative of her as an actress. Max Showalter plays her husband, the genial and oblivious Ray Cutler, who takes his lovely wife on a long overdue honeymoon, only to have it totally ravaged thanks to the Loomises. I find that many of the best Christmas movies aren’t really about Christmas at all — at least not in the conventional sense that we’re so used to. Not trees or presents or lights or even holiday sentiment although those might all be there.

I find that many of the best Christmas movies aren’t really about Christmas at all — at least not in the conventional sense that we’re so used to. Not trees or presents or lights or even holiday sentiment although those might all be there. “Heathens are not always low just as Christians are not always high.” – Gregory Peck as Father Chilsum

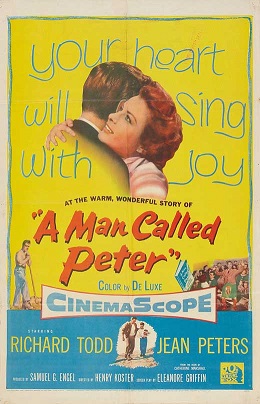

“Heathens are not always low just as Christians are not always high.” – Gregory Peck as Father Chilsum The film’s tagline reads, “Your heart will sing with joy” and that about sums up A Man Called Peter.

The film’s tagline reads, “Your heart will sing with joy” and that about sums up A Man Called Peter. Much like Sam Fuller’s Crimson Kimono (1959), Japanese War Bride’s title carries certain negative stereotypes, however, its central romance similarly feels groundbreaking, allowing it to exceed expectations.

Much like Sam Fuller’s Crimson Kimono (1959), Japanese War Bride’s title carries certain negative stereotypes, however, its central romance similarly feels groundbreaking, allowing it to exceed expectations. Jim looks to build up a happy life with her as he looks to take some of his father’s land to keep a home of his own and raise crops. Tae begins to acclimate to her new life and gains the respect of the Taylor family while making a few friends including the kindly Hasagawa siblings (Lane Nakano and May Takasugi) who work at a factory nearby. The icing on the cake is when Tae announces she’s pregnant and Jim could not be more ecstatic.

Jim looks to build up a happy life with her as he looks to take some of his father’s land to keep a home of his own and raise crops. Tae begins to acclimate to her new life and gains the respect of the Taylor family while making a few friends including the kindly Hasagawa siblings (Lane Nakano and May Takasugi) who work at a factory nearby. The icing on the cake is when Tae announces she’s pregnant and Jim could not be more ecstatic. Japanese War Bride is continuously fascinating for the presence of Japanese within its frames. First, we have a rather groundbreaking and relatively unheard of interracial romance between the always personable average everyman Don Taylor and stunning newcomer Shirley Yamaguchi. Their scenes are tender and hold a great deal of emotional impact. It’s the kind of drama that has the power to make us mentally distraught but also imbue us with joy.

Japanese War Bride is continuously fascinating for the presence of Japanese within its frames. First, we have a rather groundbreaking and relatively unheard of interracial romance between the always personable average everyman Don Taylor and stunning newcomer Shirley Yamaguchi. Their scenes are tender and hold a great deal of emotional impact. It’s the kind of drama that has the power to make us mentally distraught but also imbue us with joy.