Someone posits the following question: Are you interested in critical film theory?

My first response is what even is “critical film theory?” And I know in academic terms they are probably talking about film theory or film studies and the many strands of thought and analysis that have come out of academia in the post-war years. That’s good and fine but I would say that I am not a steadfast adherent to film theory and I’m hardly a disciple of any singular dogma, but it got me thinking at least a little bit of where I’m coming from and what my influences are.

I’m educated but hardly an academic. If I’m a critic then some would undoubtedly criticize my less than critical style. As far as film history goes, I love it! If I had to choose between any of these three entities I think I would easily take the mantle of a film historian first and foremost, although in that discipline I am an amateur. But I am a passionate amateur, self-made, self-taught and the last half dozen years or so I’ve amassed a great deal of film knowledge cramming so many cinematic facts in my head, it sometimes amazes me that I can remember most of them.

But I love the way that film is both a historical and visual medium. It can act as a time capsule taking us to different eras, places, and worlds. Introducing us to every type of person imaginable involved in every type of story. And the beauty is that even when those stories are not exactly planted in reality, they have a backstory. Actors, directors, the historical backdrop. All that plays into the film no matter the subject matter. It’s that context that fascinates me. So yes, I would probably consider myself a historian.

However, in order to get others to listen, even if it was only a very few, the need to take on the role of a film reviewer and, dare I say, a critic seemed necessary. As I said before I am self-taught so my reviews are hardly analytical in the academic sense. More on that in a moment.

In passing a few critics that I’ve admired over the years are certainly Roger Ebert, James Agee, Francois Truffaut, and more recently Alissa Wilkinson and Justin Chang. From time to time, I’ve read Kenneth Turan, A.O. Scott, Richard Brody, Anthony Lane, Matt Zoller Seitz, Eric Kohn, Leonard Maltin, Pauline Kael, Manny Farber, Vincent Canby, Andrew Sarris, Kenneth Morefield, Jefferey Overstreet, Brett McCracken, Joel Mayward, Dennis Schwartz, Jefferey M. Anderson, Tim Brayton, and some of the other prolific Rotten Tomatoes reviewers who take the time for lesser-known films.

But going back to my point of view. There’s not one perspective that I feel attached to because that’s precisely why I enjoy writing. I can put on different lenses based on the context and what I want to say. I can be formalist in my admiration for a film’s structure and composition. I can take a more contextual or cultural approach which ties into my appreciation for history, but perhaps most important to me in the progression of my own writing is what might best be described as a humanist approach. I hesitate to use this term because I would not necessarily consider myself a humanist in the generally accepted sense but I believe this lens informs my own often spiritual perspective.

Because my baseline for watching films is ultimately what they can tell me about humanity and more exactly what a film can tell me about myself, broken and confused as I am. It becomes obvious that it’s easy to criticize this perspective as being emotional and unfounded in rational thought. But I would interject that this is why I try and temper this sort of approach with the aforementioned strategies, namely formalism and historical context.

Furthermore, if I had to tie myself down to one sort of thought I guess I would have to admit paying a debt to the auteur theory which indirectly ties back to formalism. Some people might scoff at this point and that’s alright. I never admitted to being an academic or a professional critic. I just love movies and I love writing about them.

But I would say that I was influenced by the auteur theory without realizing it at first. On a practical level, it’s easy to begin cataloging and categorizing films based on their directors. You begin to take mental notes and draw up distinctions. Certainly, there are not always clear lines drawn up since a film production is made up by a lot more entities than just a director. I am astute enough to know that the director being everything is simply not the truth.

However, I would concede that in general the director, more than the screenwriter, cinematographer, or even the actors, can be the author of a film if that is their impetus. Because film is a visual medium and as the orchestrator of that process it makes sense enough that the director can utilize the script, the camera, his actors, the editing etc. to realize a certain vision. This might be artistic, commercial, or simply for entertainment but such a quality is evident in many of the most noteworthy directors. Once again, it’s easy to grab hold of a director that we like because we see certain qualities or themes or even collaborators who we really appreciate.

Another thing about the champions of the auteur theory at Cahiers du Cinema and namely Francois Truffaut is that they seemed to be attempting to put film on equal ground with other classical arts. I’m not sure what I think about that or whether that even matters but I will say that film has been and still is a powerful outlet of artistic expression.

Furthermore, the fact that these men championed underappreciated directors but also those movies and genres that might be dismissed in other circles really intrigues me. It’s this idea that no film is inherently better than another whether an Oscar winner, a foreign film, a comedy, a drama, a black and white flick or a modern blockbuster. The fact that they are different makes them interesting and they can all have merit or weaknesses on their own. So I’m allowed to appreciate a pulpy B Film-Noir as much as a prestige picture. Whatever that means.

Still further, rewinding a bit, it is the formalist theory that allows us to appreciate the work of an individual director because we can begin to pick up on and decipher themes, styles, and the like which become pervasive in their oeuvre. For instance, Hitchcock always had cameos, maintained a droll sense of humor, worked in the thriller genre almost exclusively, was concerned with innocent men on the run, crammed his plots with psychological tension, and almost always cast icy blonde actresses. On top of that, he was always one to experiment with inventive techniques and gimmicks. It makes him almost instantly recognizable. In other words, it doesn’t take a genius to latch onto his genius.

But going back to the boys at Cahiers du Cinema, I think I appreciate them not simply because they formed the backbone of the cinema-shattering Nouvelle Vague but because they put their money where their mouths were in a sense. The fact that they went from being mere critics to actually creating on their own seems to lend some credence to their words. Francois Truffaut is a striking example of this because out of all the men who came out of the movement he is probably my favorite. His films are personal, entertaining, and accessible. He loved movies too and he left his mark on each picture.

So does that clear up anything on where I stand with Film Theory, Film Criticism, and Film History? Probably not but all I ever claimed is that I really appreciate movies and that I get the privilege to write about them. Even if that writing is only for myself. That’s quite alright because I believe that I have been allowed a God-given passion for film, history, culture and the like. It’s this joy that I want to share with others to cultivate relationships and dialogue with all sorts of people. Because each one of us has worth, despite our very shortcomings. Once more, that’s once and for all why I watch movies (Side Note: This is also why I write humanistically).

Thanks for listening to me pontificate on this seemingly arbitrary topic. I promise this will be one of the few times. After all, that’s not what I want my modus operandi to be. Soli Deo gloria.

I said a while back that I wanted to acknowledge a few living legends who are still with us in a series of short posts and I’ve finally gotten around to it. Enjoy!

I said a while back that I wanted to acknowledge a few living legends who are still with us in a series of short posts and I’ve finally gotten around to it. Enjoy! As I’ve grown older and, dare I say, more mature, I like to think that I’ve gained a greater appreciation for those moments when I don’t understand, can’t comprehend, and am generally ignorant. Now I am less apt to want to beat myself up and more likely to marvel and try and learn something anew. Thus, Marienbad is not so much maddening as it is fascinating. True, it is a gaudy enigma in form and meaning, but it’s elaborate ornamentation and facades easily elicit awe like a grandiose cathedral or Renaissance painting from one of the masters. It’s a piece of modern art from French director Alain Resnais and it functions rather like a mind palace of memories–a labyrinth of hollowness.

As I’ve grown older and, dare I say, more mature, I like to think that I’ve gained a greater appreciation for those moments when I don’t understand, can’t comprehend, and am generally ignorant. Now I am less apt to want to beat myself up and more likely to marvel and try and learn something anew. Thus, Marienbad is not so much maddening as it is fascinating. True, it is a gaudy enigma in form and meaning, but it’s elaborate ornamentation and facades easily elicit awe like a grandiose cathedral or Renaissance painting from one of the masters. It’s a piece of modern art from French director Alain Resnais and it functions rather like a mind palace of memories–a labyrinth of hollowness. In fact, although this film was shot on estates in and around Munich, I have been on palace grounds similar to the film. There’s something magnificent about the sprawling wide open spaces and immaculate landscaping. But still, that can so easily give way to this sense of isolation, since it becomes so obvious that you are next to nothing in this vast expanse. Marienbad conveys that beauty so exquisitely, while also paradoxically denoting a certain detachment therein.

In fact, although this film was shot on estates in and around Munich, I have been on palace grounds similar to the film. There’s something magnificent about the sprawling wide open spaces and immaculate landscaping. But still, that can so easily give way to this sense of isolation, since it becomes so obvious that you are next to nothing in this vast expanse. Marienbad conveys that beauty so exquisitely, while also paradoxically denoting a certain detachment therein. Do we understand this bit of interaction at this stately chateau? Probably not. In fact, I’m not sure if we are meant to know the particulars about last year in Marienbad. That doesn’t mean we still can’t enjoy it for what it is. Because Alain Resnais is perennially a fascinating director and he continued to be for many years. Whether you think this is a masterpiece or a piece of rubbish at least give it the courtesy and respect it is due. Then you can pass judgment on it, whatever it may be.

Do we understand this bit of interaction at this stately chateau? Probably not. In fact, I’m not sure if we are meant to know the particulars about last year in Marienbad. That doesn’t mean we still can’t enjoy it for what it is. Because Alain Resnais is perennially a fascinating director and he continued to be for many years. Whether you think this is a masterpiece or a piece of rubbish at least give it the courtesy and respect it is due. Then you can pass judgment on it, whatever it may be. It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on.

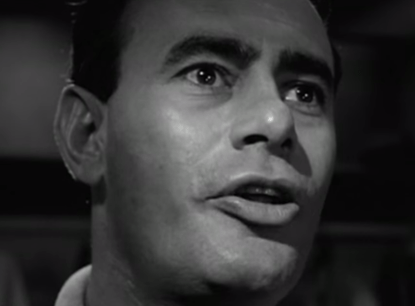

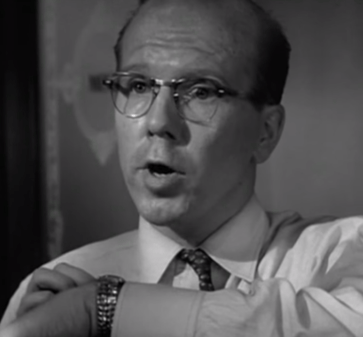

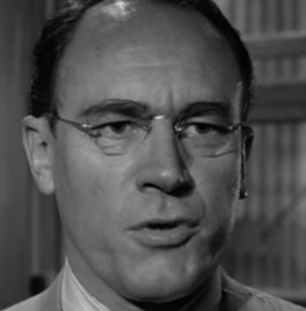

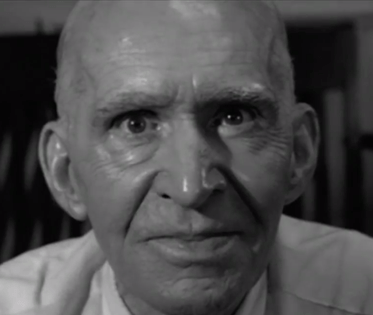

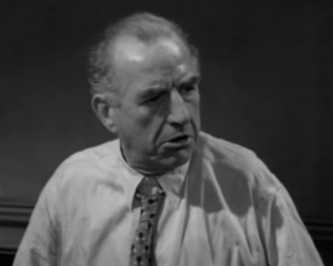

It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on. The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat.

The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat. But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale.

But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale. We are met with a deluge of drums, explosions, and the unmistakable voice of Bono murmuring over the credits. The year is 1974 in Guilford England, the Irish Republic Army is as belligerent as ever, and right from the beginning director Jim Sheridan’s In the Name of the Father grabs hold of our attention.

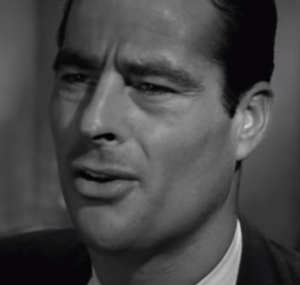

We are met with a deluge of drums, explosions, and the unmistakable voice of Bono murmuring over the credits. The year is 1974 in Guilford England, the Irish Republic Army is as belligerent as ever, and right from the beginning director Jim Sheridan’s In the Name of the Father grabs hold of our attention. But what follows is something out of some perverse nightmare. Upon a return trip back to Belfast Gerry finds his home raided and he ends up in the interrogation block being grilled by a group of less than sympathetic police attacking him with a barrage of insults and threats. This doesn’t just seem like an Irish-English problem. There’s so much hatred present and Conlon and three of his buddies get roped into signing confessions under duress.

But what follows is something out of some perverse nightmare. Upon a return trip back to Belfast Gerry finds his home raided and he ends up in the interrogation block being grilled by a group of less than sympathetic police attacking him with a barrage of insults and threats. This doesn’t just seem like an Irish-English problem. There’s so much hatred present and Conlon and three of his buddies get roped into signing confessions under duress. However, as he has the habit of doing Daniel Day-Lewis falls so seamlessly into his role as the Irish lad from Belfast who was wrongly accused. His Irish brogue is second-nature and he jumps between rebelliousness and fear with tremendous skill due to the emotional range demanded by the role.

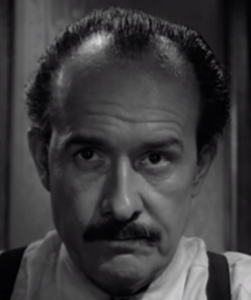

However, as he has the habit of doing Daniel Day-Lewis falls so seamlessly into his role as the Irish lad from Belfast who was wrongly accused. His Irish brogue is second-nature and he jumps between rebelliousness and fear with tremendous skill due to the emotional range demanded by the role. This is an Otto Preminger film about politics. That should send off fireworks because such a divisive topic is only going to get more controversial with a man such as Preminger at the helm — a man known for his various run-ins with the Production Code. All that can be said is that he didn’t disappoint this time either.

This is an Otto Preminger film about politics. That should send off fireworks because such a divisive topic is only going to get more controversial with a man such as Preminger at the helm — a man known for his various run-ins with the Production Code. All that can be said is that he didn’t disappoint this time either. As the film opens we watch a foot slowly wiggling its toes. It’s nothing extraordinary because we’ve undoubtedly seen this millions of times. If not on film then at least in our own lives. But it’s what the foot does that piques our interest. Quite dexterously but still straining, it manages to pull a record out of its sheath, set it down on the player, and lay down the needle before music finally emanates out. This simple act gives us some profound insight into the story that we are about to invest ourselves in.

As the film opens we watch a foot slowly wiggling its toes. It’s nothing extraordinary because we’ve undoubtedly seen this millions of times. If not on film then at least in our own lives. But it’s what the foot does that piques our interest. Quite dexterously but still straining, it manages to pull a record out of its sheath, set it down on the player, and lay down the needle before music finally emanates out. This simple act gives us some profound insight into the story that we are about to invest ourselves in. Peter Pan was immortalized by Disney in 1953, but as with many of the great fairy tales that they have adapted, it’s easy to forget that there was an earlier spark. These stories do not begin and end with Disney. They have a far more complex origin story and ensuing history. So it goes with J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan.

Peter Pan was immortalized by Disney in 1953, but as with many of the great fairy tales that they have adapted, it’s easy to forget that there was an earlier spark. These stories do not begin and end with Disney. They have a far more complex origin story and ensuing history. So it goes with J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan.