“Smile” is a timeless hit among a plethora of classic Nat King Cole tracks. The innate warmth and the soothing nature of his vocals shine through every note. It took me many years to realize the tune was actually a Charlie Chaplin composition from City Lights later reworked with lyrics.

“Smile” is a timeless hit among a plethora of classic Nat King Cole tracks. The innate warmth and the soothing nature of his vocals shine through every note. It took me many years to realize the tune was actually a Charlie Chaplin composition from City Lights later reworked with lyrics.

However, this is not a review of The King or The Tramp. It is about a movie, but to consider it, one must acknowledge the song is so very sincere, it can be used in highly ironic ways.

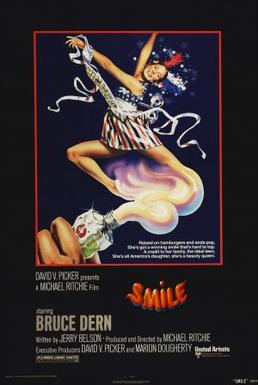

Case in point is Smile the movie, which was obviously fashioned as a genteel satire of Miss America culture.

It is a depiction of a different America that we can never go back to. Sometimes those words might sound wistful though, in the case of Smile, it’s more of an assertion. Because this lightly-handled prodding of societal mores, full of its share of cutesy and sickening moments, is really a commentary on a very suspect culture.

Still, one must ask the question: how much does the industry get inadvertently glorified by such a comedic extravaganza throwing all these young girls, harried folks, and inquisitive onlookers into an environment complete with plenty of pizzazz and a full-fledged happy ending?

There’s a moderate danger of missing the point — even if it is twofold. We can laugh or “smile” but we must also consider how ludicrous this all is. Thankfully the movie is aided by some of its wonkier inventions in case we’re tempted to take it at face value.

Smile is, of course, easily overshadowed by Nashville (1975) with its more discernible social significance, a grander ensemble, and a lot more going for it on all fronts. That’s not to say Smile is a bad movie. In fact, it is probably an underrated one, generally forgotten with the myriad of other 70s entertainment options moviegoers will normally flock to.

The story itself has the ring of something terribly agreeable. It’s a lightweight day-to-day observation of the annual Young American Miss Pageant in beautiful Santa Rosa, California. All the would-be “Misses” are bussed in to take part in the competition and all the laurels that come with such a crown.

Their hearts are a tizzy with excitement. Former champion Brenda DiCarlo (Barbara Feldon) knows just the feeling. Her advice is, as always, to “smile” as she helps to prepare the girls for their exhibition (which is not a competition). Although everyone knows otherwise.

Meanwhile, a Hollywood choreographer (the esteemable Michael Kidd) is brought in to work on the routines, the janitor worries about the undue stress that will be put on the pipes, and local used car salesman Big Bob Freeloader (Bruce Dern) gets ready for his civic responsibility to judge the contest.

He’s the epitome of a square, wheeler-dealer, car salesman who in his own way sees himself as a pillar of society, even if he helps to propagate the dubious cultural practices of the times.

His son, “Little Bob,” looks to snag a polaroid camera with his friends so they might capture the recently arrived pageant hopefuls in various states of undress. Though played for comedic effect, it really is a jarring, uncomfortable digression.

Because already implicit in the content are the strains of mid-century misogyny, essentially built into the fabric of society. It begins with the grown-ups as good, healthy All-American fun, until it easily seeps down to their children, teaching boys how they are to perceive girls.

Simultaneously, the local male fraternity initiation feels dangerously close to a white supremacist meeting, albeit with strange rituals (ie. kissing a dead chicken). On the ethnic front, the one non-Caucasian character, a Mexican-American, is looked on with immense derision by all the others and with the depiction, I wouldn’t blame them.

Her starry-eyed ambitions to be American are seen in a handful of characters, though she’s the only one hampered by a pointed accent. Again, it’s these obvious red lights that are being poked fun at. There’s little question about it, but if these are the issues we are dealing with, there are still other de facto problems that probably slip through the cracks.

It has not aged well even as we still have rampant issues of sexual objectification and any number of prurient problems. It could be very well that I am not in touch with the current cultural moment. If so, I stand corrected. But the odd mixture of nostalgia with light satire does come off as a weird, messily concocted cauldron of tones.

The free-flowing contact with the wide range of characters also means we never ably connect with anyone in a resonant manner. Likewise, director Michael Ritchie’s story, like The Candidate before it, is taking aim at society but in this instance, it feels like there are too many marks. It cannot cover all the ground and, therefore, feels a bit scattered.

Unfortunately, it’s lost some of its comic zing with the passage of time. Still, one of the finest bits of humor comes in an outrageous sequence when a man looks to end his life with a pistol.

His wife the former American Miss tells him he should deal with his problems instead of taking the coward’s way out. He proceeds to point the gun at her and let it go. He winds up in jail and she’s only scratched, agreeing not to press charges, much to his chagrin.

In fact, Andy DiCarlo might be the most genuinely enjoyable character for the very reason he sees the utter insanity of this world, even if everyone else brushes him off as being a little strange.

They think he needs to loosen up some like all his peers, kissing the butts of dead chickens and cheering for girls paraded up on a stage like glorified cattle. Now that’s entertainment! In this light, Smile does sound somewhat hilarious. Chalk it up to a misanthropic mood if you want. However, I’ll maintain people weren’t made to always be smiling. Sometimes a smile just won’t cut it.

3/5 Stars

NOTE: As a childhood Get Smart fan, I tried not to hold it against Smile for casting Barbara Feldon in her part. I tried my best to be objective, but, for me, she will always be 99.

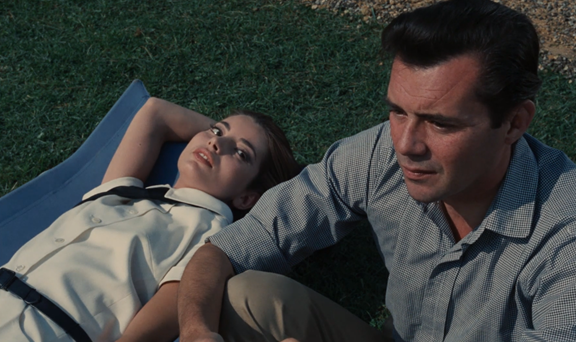

I am tempted to call The Swimmer a pretentious fable about the waters of life. It is set in the upper echelon of Connecticut society, but the same cross-section might hold true in California as well. In fact, one could say this film effectively extends the pool metaphor of

I am tempted to call The Swimmer a pretentious fable about the waters of life. It is set in the upper echelon of Connecticut society, but the same cross-section might hold true in California as well. In fact, one could say this film effectively extends the pool metaphor of

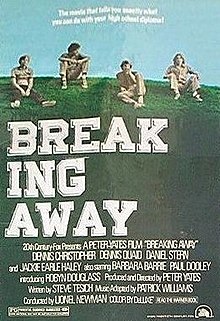

“When you’re 16, they call it sweet 16. When you’re 18, you get to drink, vote, and see dirty movies. What the hell do you get to do when you’re 19?”

“When you’re 16, they call it sweet 16. When you’re 18, you get to drink, vote, and see dirty movies. What the hell do you get to do when you’re 19?”