Growing up in a household indebted to British everything, you get accustomed to certain things. Numerous everyday knickknacks and antiques imported from The U.K. Muesli Cereal in the pantry with copious amounts of English Breakfast Tea. Beatrix Potter, P.G. Wodehouse, and Postman Pat become household favorites.

Growing up in a household indebted to British everything, you get accustomed to certain things. Numerous everyday knickknacks and antiques imported from The U.K. Muesli Cereal in the pantry with copious amounts of English Breakfast Tea. Beatrix Potter, P.G. Wodehouse, and Postman Pat become household favorites.

Particularly at Christmastime, this meant, no, not figgy pudding, but British Christmas Carols on record. Some of my personal favorites are probably “Sussex Carol,” “Ding Dong Merrily,” “Past Three O’Clock,” and of course, “The Holly and The Ivy.”

This is where the film gets its namesake as it follows the Gregory family during the holidays. It’s that time of year with everyone convening for Christmas at a vicarage in the cozy town of Wyndham, nestled in Norfolk.

It sounds like a delightful experience, and it gains even more prominent meaning for a lonely old matron — airy and grandiose of tone — as she’s grateful for the letter from her brother-in-law confirming she will not have to spend the holidays alone. Cue the swelling music.

At this point, if you assured me The Holly and The Ivy wasn’t a sentimental movie I probably would have disregarded you. This is before the rug is literally pulled out from under us. For now, we still have a ways to go.

Quite by chance, during the pilgrimage aboard a train, she bumps into the other aunt, the acerbic and proud Aunt Lydia a world-class misanthrope. Despite they’re differences, they do well to cancel each other out. You can only imagine what might happen if you put them with others.

Sure enough, there’s a philandering young soldier who is caught by his superior with a girl and winds up in a whole lot of hot water. However, by some curious circumstance, he’s able to worm his way out and get leave to see his family for Christmas. This rapscallion is, of course, Michael Gregory (Denholm Elliot). It is his father who runs the local vicarage in Wyndham.

Jenny Gregory (Celia Johnson) is the devoted daughter who runs her father’s home and takes care of all his affairs. She feels this is her duty while he is still working and his other sister lives away in London all but detached from the rest of her family. The main complication is the man Jenny loves is about to realize his lifelong dream of working in South America. It will be five long years and though Jenny is dying to go with him, her hands are tied.

When we finally meet Reverend Martin Gregory (Ralph Richardson), it becomes apparent he’s a bit absent-minded and quite the chatterbox. He goes on and on about his fascination with the Incas and their ingenuity in using Guano (bird droppings). He, of course, knows nothing about his daughter’s situation because no one has told him anything and so he remains oblivious going off to view the nativity play at his church (a fine precursor to Charlie Brown’s Christmas).

This is one of the great tragedies running through the story. The reverend himself bemoans the fact parsons are set apart and isolated because of their vocation. There is an inherent awkwardness going out into the world as a man of the cloth. People don’t want you around. It makes them feel uncomfortable and yet in the same breath, they hold you to a different standard because you are meant to represent religious piety for all.

But there is also an undercurrent in his home. His children never tell him how they are really doing. They equivocate and keep things hidden in order to not upset him or receive his scorn. Because that is how they see him. He is a killjoy, someone put in their life to chide them and scold them for every one of their individual sins. The fear is if he actually knew what his children were like, he would be unbearable. It certainly is a problem in conservative environments where exteriors don’t mesh with interior issues.

It comes to a head when the sister Margaret straggles in late to the festivities. They made up a lie about why she wouldn’t be able to come and yet the real truth is she did not want to see her father. But the wounds and the hesitance run deeper still. She is an alcoholic and something else happened to her. Those who love her, note she crackles like ice — a frozen ice queen out of a Hans Christian Andersen story.

Reverend Gregory has reason to be dismayed that Christmas in merry ol’ England is now ruled by the boars and the retail traders who have gotten hold of the season. He laments, “It’s all eating and drinking and giving each other nicknacks…No one remembers Jesus Christ.” It teeters along the precipice of righteous indignation.

Because he looks at the same people and sees how little use they seem to have for him even when he sees, what he deems to be, great need. He’s there to marry and bury them only. His church is only an architectural center, not a spiritual one. This right is reserved for the local movie house with all its enticing bells and whistles.

While he might have a point, he is just as implicated in the problem; he has exasperated society. The case study is found in his family. We see it in so many cases. The religious figure is measured by a separate set of principles and yet because of what we place on them, they feel distant and unreachable. They make us feel dirty and ashamed of our improprieties.

David blasts his father telling him, “You can’t be told the truth. That’s the trouble!” It’s films such as these that make me realize how difficult it would be to be a religious leader. Likewise, it’s just as difficult to have to live life alongside them — at least in a case like this.

Where “every conversation goes back to the creation of the world” and our only way to keep up appearances is lies and concealment — a life of false pretenses just in time for the holidays. The holidays only serve to magnify the tensions brooding for so long.

Because sons find the faith and fairy stories antiquated. Fathers are vexed that everything must be seen and touched in this generation before it can be believed (Can you touch the wind?)

The beauty of the exploration is in how both sides are given some credence. How can parsons expect to be told the truth when one can’t even talk to them like ordinary human beings? How can common, everyday people who make mistakes be free from guilt and shame when the most common judgments are full of condemnation?

While not of the same technical prowess, it nevertheless reminded me of Ordet another film based on a stage play with deep recesses of spirituality. There are a myriad of relationships undone by doubts and perceived areas of incompatibility. In fact, it falls somewhere between Ordet and Calvary because it has a dose of empathy for both the parson and his family.

The miracles revealed are ultimately conversational and sweet, reviving family relationships and salvaging the season through reconciliation. Wounds and secrets so long harbored and festering are finally allowed into the light. The extraordinary thing is, far from sowing more discord, the honesty gives way to the first true peace they’ve had for years.

My only qualm is I rather am curious to hear Ralph Richardson’s sermon. Like David Niven in The Bishop’s Wife, there’s a sense it might have been something magical and deeply impactful to behold. More powerful still, his words live on in the imagination.

The ending comes rapidly but it is reassuring to get one final image of the church with the newly minted couple destined to be together — most everything restored. Because filling in the ending, especially under such jocund circumstances, is often one of the greatest gifts that can be extended to the audience.

4/5 Stars

In viewing the 1951 version of the Christmas classic, I took particular interest in the name of our protagonist Ebenezer Scrooge, attempting to redeem it for the masses. For this picture, I was curious in considering another integral term in our lexicon: Humbug.

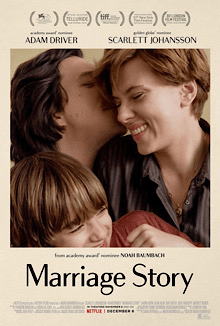

In viewing the 1951 version of the Christmas classic, I took particular interest in the name of our protagonist Ebenezer Scrooge, attempting to redeem it for the masses. For this picture, I was curious in considering another integral term in our lexicon: Humbug. In full transparency, I’ve often considered Noah Baumbach as heir apparent to Woody Allen and a lot of this attribution falls on their joint affinity for New York City. It is the hub of their life and therefore their creative work even as the broader art world often finds itself seduced by the decadent riches of Los Angeles.

In full transparency, I’ve often considered Noah Baumbach as heir apparent to Woody Allen and a lot of this attribution falls on their joint affinity for New York City. It is the hub of their life and therefore their creative work even as the broader art world often finds itself seduced by the decadent riches of Los Angeles.