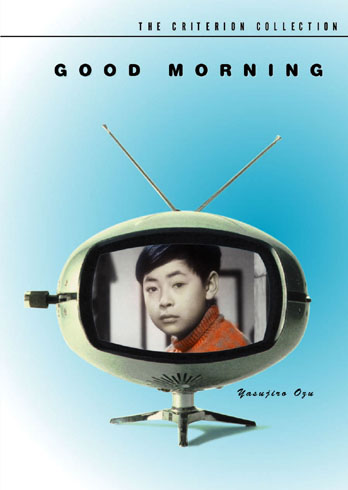

If Yasujiro Ozu can be considered foremost among Japan’s preeminent directors then there’s no doubt that Ohayo (Good Morning in English) is one of his most delightfully silly films. But that’s only on the surface level.

If Yasujiro Ozu can be considered foremost among Japan’s preeminent directors then there’s no doubt that Ohayo (Good Morning in English) is one of his most delightfully silly films. But that’s only on the surface level.

Young boys are unified in their affection for watching sumo on television and passing gas as a great gag to pull on their friends. Nosy housewives gossip incessantly whether it be the next door neighbor’s new washing machine or the mysterious disappearance of dues for the local women’s association. Meanwhile, most of the men go to work and spend their evenings knocking a few back at the bar noting how much the world is changing around them. Then they go home oftentimes a little drunk.

Ohayo is actually a reimagining of one of Ozu’s most remembered early pictures during his silent days I Was Born But… (1932) and yet he skillfully reworks the storyline into an everyday comedy of family and neighborhood drama that’s full of humor and his brand of quietly observant social commentary.

Ozu always took great care in analyzing family units and matrimonial bonds that affected relationships. Although we have a bit of a fleeting young romance in the works, this film’s greatest concern are two young boys from the Hayashi family who are giving their parents the silent treatment until they are allowed to have a television. Their parents are holding out and it begins a rather humorous ordeal as the brothers Minoru and the ridiculously comical Isamu (constantly exclaiming “I Love You”) try to make it through dinner, school, and so many other daily activities without a word.

As he would dissect many times over, Ozu focuses on the generational divide that was emerging and becoming increasingly prevalent in the post-war years as reflected by technological advancements like television and other such devices slowly turning present Japan into a land of a million idiots. At least that’s what the older generations feel.

Still, it’s just as equally occupied with the moral customs that have long ruled the nation where wives can speak so kindly to their neighbors up front only to slander them behind their backs a moment later. Saving face and personal honor is often cared about far more deeply than anything else — even in some circumstances when it happens to be at the expense of another family member.

Perhaps the most troubling thing is the very Japanese predilection to talk about nothing in particular, filling conversations with salutations, pleasantries, and comments on the current weather patterns. It hardly ever gets to anything of substance and that comes in numerous forms. Sometimes it means a young man never gets around to sharing his feelings with a girl or adults never being particularly candid with neighbors or spouses. There’s very little of that kind of transparency to be had. Few of the words passed along between people in conversation mean all that much.

The irony of the whole situation is that, in one such instance, it’s a young son who calls them out on it and he proceeds to get a heavy scolding from his father (Chishu Ryu) who bluntly tells him that he talks too much. Meanwhile, although Izamu can be constantly chiming “I Love You” in English, there’s an uneasy sense that his parents and most certainly his father, might have never said the words to him.

In these very simple ways Ozu rather delicately and still humorously tackles many of the issues that have long plagued an honor-based culture such as Japan’s but he does it with an adroitness that uses touches of humor and his own understanding of human nature to craft yet another universal tale that’s ultimately sympathetic in its portrayals.

It unsurprisingly feels like it could be a Japanese episode of Leave it to Beaver except for the father never has much of a talking to with his sons and the mother may be as put together as June Cleaver but hardly feels ever as affectionately maternal.

Equally spectacular is Ozu’s mise-en-scene which as per usual is meticulously staged and gorgeous in scene after scene. He offers up each individual image in a flat two-dimensional way that can best be described as taking cues from not only the theater but Japanese woodblock paintings with wonderful symmetry and compositions boosted by color.

He uses the clique of adjoining homes as the perfect set to send his characters in and out of with the hint of comedic forethought. While watching characters walking by on the hillside up above the homes — their figures slowly moving in and out of the frame past the houses — this provides some of Ohayo’s most visually stimulating images pleasing the eye incessantly.

There’s always a visual fearlessness that you see in very few others because he not only has color at his disposal but the staging is on point as is his disregard of the 180-degree rule of perspective. It just works. What is more, he also continues to use what could best be called establishing shots by western audiences. Except they hardly ever need to establish anything. It’s as if he simply put them there because they are vivid depictions of the reality he is painting — adding yet another distinct contour to the world he is working with — going beyond the figures that he places within the frame.

There’s no doubt that this is Ozu but not all that surprisingly this might be my personal favorite in his oeuvre for the aforementioned reasons. It feels like Ozu operating at his most playful while nevertheless maintaining his peak form as a filmmaker.

4.5/5 Stars

It’s not something you think about often but stoners and film noir fit together fairly well. Why more people haven’t capitalized on this niche is rather surprising. Think about it for a moment. Film noir in the classic sense is known for its private eyes, femme fatales, chiaroscuro cinematography, and perhaps most importantly a jaded worldview straight out of Ecclesiastes.

It’s not something you think about often but stoners and film noir fit together fairly well. Why more people haven’t capitalized on this niche is rather surprising. Think about it for a moment. Film noir in the classic sense is known for its private eyes, femme fatales, chiaroscuro cinematography, and perhaps most importantly a jaded worldview straight out of Ecclesiastes.

Entering into the latest Avengers blockbuster I felt like I was missing something thanks to a cold open that places us in an unfamiliar environment. It’s a feeling that has come upon me on multiple occasions previously.

Entering into the latest Avengers blockbuster I felt like I was missing something thanks to a cold open that places us in an unfamiliar environment. It’s a feeling that has come upon me on multiple occasions previously.