The 1950s saw director Vincente Minnelli continually evolving from mostly musicals — a pleasing genre he never totally forsook — into a period of his career ripe with luscious Metrocolor dramas.

Movies such as Tea and Sympathy, Some Came Running, and Home from the Hill, don’t get too much coverage in broader circles, especially compared to Oscar darlings like An American in Paris or Gigi. However, in many ways, they’re equally interesting, if not more so.

As the story opens on a prep school green, it proves the world still had class reunions generations before and if the content was different, the people aren’t all that dissimilar. Tom (John Kerr) is someone we get to know quite well over the next two hours.

However, we are only introduced to him because Minnelli’s camera cycles to him as he traverses his former stomping grounds. While not prototypically Hollywood handsome like John Saxon or George Hamilton, Kerr is incessantly interesting and easier to project our own insecurities onto. He’s a bit severe, more awkward, but able to imply a certain sensitivity.

He ventures into his old dorm and all the memories come flooding back. Minnelli doesn’t go with a dissolve or a fade-out, but he moves his camera through the window down to the grass below as if we are entering into an entirely different world, and in a sense we are.

The space is the same but the years have gone and faded back into the past for us. Deborah Kerr works away cultivating her garden as John Kerr (no relation) eagerly looks to offer her any assistance. It’s plainly apparent he has a major crush on the teacher’s wife.

Those unfamiliar with the play might think they already have an inkling of what this picture is about, young unrequited love, adolescence blooming into adulthood. There are elements of this, but Tea and Sympathy becomes far more groundbreaking and pressing in turns.

Because Tom Robinson Lee is totally ill at ease around girls; he can’t dance, and he’s slated to wear a dress in his school’s latest stage production. Don’t try and explain to his peers what the Greeks and Japanese used to do on stage. He’s a sorry excuse for a man; that’s what he is.

It’s an equally awkward situation when he makes fast friends with the faculty wives — Mrs. Reynolds among them — and she tries to be gentle and kind to him. Because he’s really a decent boy. He gladly shares among this company that he can sew and cook showing them his skills with a needle and thread.

The jocular Mrs. Sears (Jacqueline DeWitt) jokes, “You’ll make some girl a good wife.” These are all tiny barbs of cinematic emasculation that cannot go totally unnoticed. It’s difficult for them not to have a cumulative effect.

Sure enough, he’s found out when some of the boys playing football along the beach see him, and he’s quickly in danger of being labeled. Because Tea and Sympathy is a movie totally immersed in the mores of the 1950s. These are issues of masculinity and gender roles altogether intensified by the furnace of contemporary societal pressure.

Because further down the shoreline, the boys toss around a football, roughhouse, and read off questions in an “Are You Masculine” quiz led by Mrs. Reynolds’s he-man husband (Leif Erickson). The news of Tom spreads like wildfire, and he earns his ignominious name “Sister Boy.” It’s the kind of reputation that does not die easily. His bedroom door is marked and he’s roughed up all in the testosterone-induced fun of boys both raucous and cruel.

You would think he could regain some respect out on the tennis court the following day, routing his opponent, but even this is hardly enough to burnish his reputation. It’s made more awkward by a visit from his dad, who can sense that the “regular guys” are against him. Of course, “regular” becomes code for being complicit in this debilitating sense of peer pressure ruling the school and its generational legacies.

Edward Andrews has a kind of easy southern charm both somehow outwardly genial and still riddled with so much dysfunction. He chides Tom that you’re known by the company you keep. He should get a crewcut and take part in the pajama fights which are like a rite of passage. There’s something to be said for conformity — becoming one of the boys as it were.

Still, the town has changed since he was a boy. They sit at the counter of the local watering hole as the long-suffering waitress Ellie is kidded and harassed incessantly as she tries to work the tables. His dad feels some amount of vicarious humiliation seeing how much of a social pariah his son seems to be. It makes him uneasy.

It’s a bit of a visual cheat, but it’s also one of the most effective set-ups in the movie as Mrs. Reynolds goes in to grab the drinks in the kitchen, and she hears the conversation coming quite freely through the window as the two men talk about the young men. Mr. Lee and Mr. Reynolds were mates in the old days and they aren’t above speaking plainly about him — how different he is. It’s obvious their words burden Laura’s heart; we see the empathy building over her face because the men don’t understand.

If it’s not apparent already, the whole system they are devoted to is broken to its core. For this boy sewing is his sin. In retaliation his peers take a stance. Since he’s not one of them, one of their tribe, he must become the scapegoat to reaffirm their shaky position.

Keeping in line with this, faculty wives are supposed to remain bystanders providing only a little tea and sympathy. A giant pyre is lit in the middle of the commons setting the stage for a pajama fight — something that has been passed from generation to generation.

From a cinematic standpoint, there’s this underlining tension to the event reminiscent of the Chickie Run from Rebel Without a Cause. It suggests something fated and inevitable about what they do — what they subject themselves to. Isn’t it in the earlier film where one boy says, “You‘ve gotta do something. Don’t you?” Here it’s institutionalized.

For a time, Al (Daryl Hickman) is Tom’s roommate and his only advocate. Mrs. Reynolds speaks to Al in admiration; he showcases physical vs. moral courage, and yet it’s lonely pushing against the social currents. Even his father admonishes him. He must be a nail hammered back into place — a place of conformity.

Mrs. Reynolds acknowledges to her husband that they don’t seem to touch anymore. There’s a distance between them, and it only grows darker and colder as the picture progresses. As we find out, her first husband died during The War: “In trying to prove himself a man, he died a boy.”

Tom is stricken by the same path. He vows to meet up with Ellie, the town’s tramp to prove his mettle as a misogynistic boy’s boy. Surely this is the only way he can prove himself and meet their standards — the standards of his own father. It’s not worth documenting the whole sorry affair. It’s garish, unseemly, and pitiful. Production Codes or not, Tom wants real love and affection. This isn’t it.

His father shows up again puffed up with pride for the first time in a long while. Because his boy has gone and got himself expelled for being off-campus with an undesirable woman. It’s like a badge of honor — being out of bounds — and showing off the extent of his masculinity, whether real or imagined. It doesn’t matter to Mr. Lee as long as he can imagine his boy being made in his own contorted image.

However, the picture suddenly does something remarkable. It seeks refuge resorting to its only comfort. The scene where Laura comes upon Tom kicked back, lounging in the forest leaves the scholastic world behind altogether for the ethereal and the sublime.

It loses any semblance of ’50s hothouse and forsakes the visible emotions of Metrocolor for something intimate and serene. Laura’s final charge to the boy is plain — be kind.

I wasn’t sure what I thought about Tea and Sympathy as it dissolved back into the present. Of course, the way the film was structured, it was necessary, and yet it seemed like the import was already made evident in an embrace between two people. What more did we possibly need?

But as Tom finds the letter and reads its contents, what looks to totally ruin the movie with moralism is augmented by two aspects. Minnelli’s camera begins to move, capturing the wind rustling through the trees and floating through the open spaces giving them a sense of pensive reverie of a different kind.

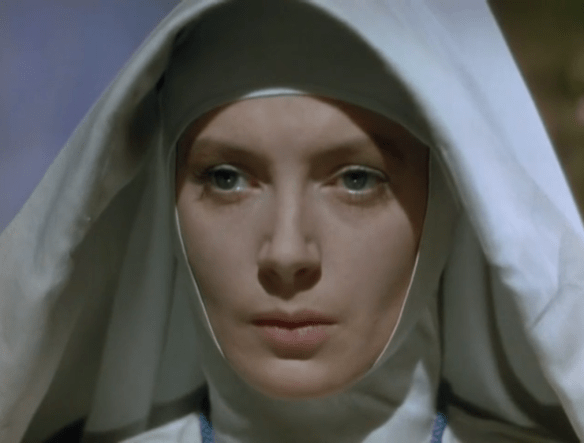

Deborah Kerr’s line reading is spot on. No one else could deliver it in such a way making it bear all the warmth and truth in a manner that feels entirely genuine.

Her character reframes everything we have seen and instead of simply placating the production codes, it feels like she is delivering some sagacious bit of nuance Tom might only understand with the passage of time.

She is so important to this picture, and she blesses it with her usual poise and grace helping to fill the void in a movie lacking a great deal of goodness. She becomes its primary beacon even as she looks for goodness for herself.

Given its themes, it would be easy for the film to become a totally salacious, opportunistic bit of illicit love. But in part thanks to Kerr and Minnelli’s care, it never becomes relegated to such status. It represents something much more.

I couldn’t stop thinking about this idea of moral courage. Tea and Sympathy somehow exhibits how one goes about it. It’s not simply about being counter-cultural or going against the tides of the times or being progressive. There is such a thing as goodness, as kindness, as gentleness — fruit we can see in our lives.

It has nothing to do with signaling our virtues, how positively or negatively others will perceive us, or the identity we look to embody. My hope is that even while our society evolves, growing further enlightened, fickle, and oppressive in various turns, we might learn what it is to have unwavering moral courage.

It’s a struggle, but it’s simply the best way to love others well, providing something more than merely tea and sympathy. Because this is not a healthy formula to help assuage the world’s ills. We require something far better.

4/5 Stars