It’s a private fascination of mine to consider the sanctity and sheer awesomeness of human life in a very particular context. How parents pass on their genes — a package of habits and physical phenotypes to their kids — that we can then witness before our very eyes. And this is even true of those who are dead and gone. Their children remain as a testament to who they were and still remain in our hearts and minds. By no means a carbon copy, but you can look into their eyes or see a photo and observe a brief glimpse of the person you knew before who is there no longer.

In some circuitous way, Pilgrimage becomes a story partially about this type of lingering memory. It is a journey and it involves certain people, but it evolves into something quite different than what I was expecting and this is to its credit. Allow me to explain.

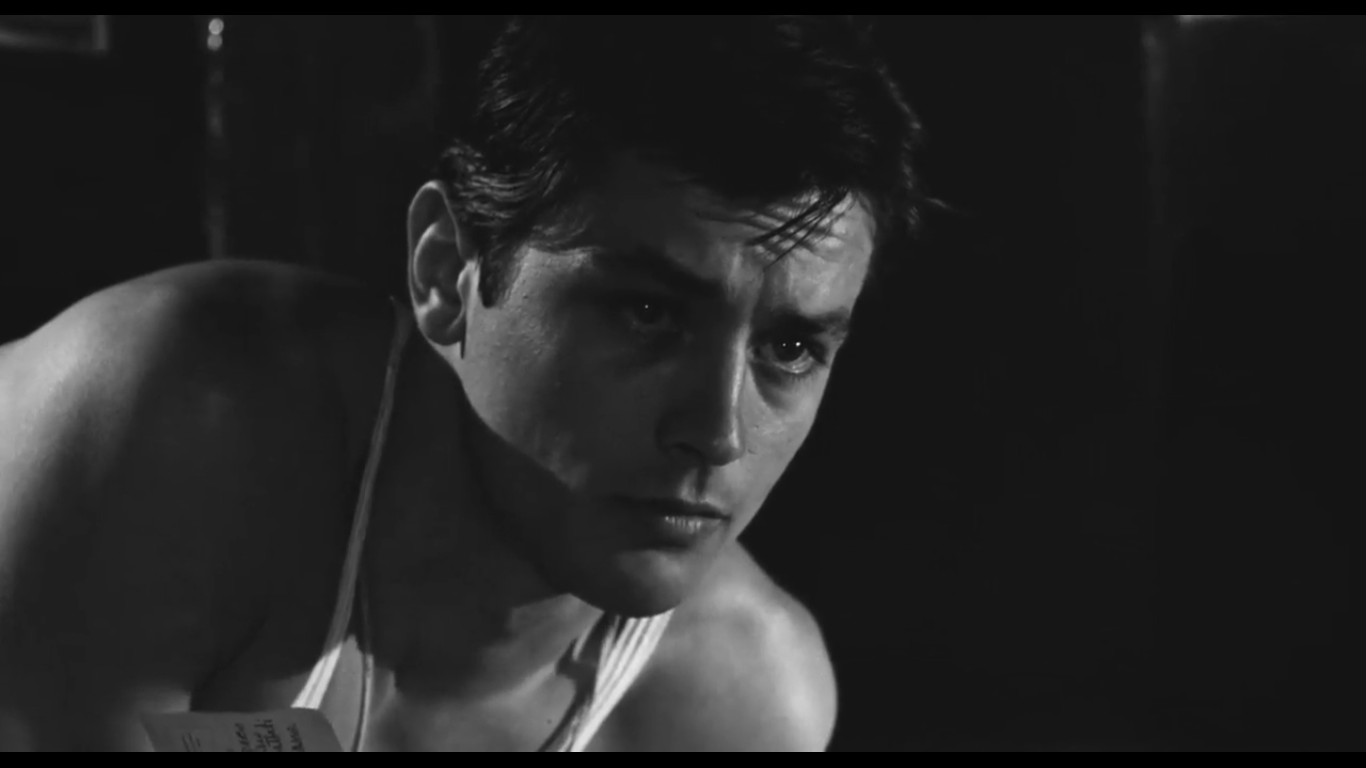

It’s one of those rural tales set in Three Cedars, Arkansas on the farmland of Hannah Jessop (Henrietta Crosman). The dynamic is simple. She’s a hard-bitten mother who’s lived a rugged life running her farm. Her son (Norman Foster) is a strapping, fresh-faced man in love with the girl (Marian Nixon) down the road and remains discontented with a life in the fields. There’s a chafing between mother and son.

She’s not going to let him marry a “harlot,” though there’s a distinct possibility she would never agree to any girl he chose to marry. Furthermore, she can’t understand how her boy can be so ungrateful and would willfully defy her. It’s a generational divide opening between them.

Watching a Ford picture, you’re waiting for those individual moments you can take with you. I’m thinking of Henry Fonda leaning up against the post in My Darling Clementine. John Wayne trotting off into the foreground at the end of The Searchers. In Pilgrimage, I’m reminded of a man sitting on his bed as he plays around with his dog — playfighting and having the animal crawl through his open arms.

It’s actually a mechanism for biding time because he waits for his mother to fall asleep so he can drop out of his second-story window and race off to be with his love. Earlier, during their first official meeting in the movie, there are a pair of memorable subjective camera shots when the two lovers come upon one another with a pond between them.

I’m adding my own emphasis, but it’s as if to say this is supernal love — love supreme — and its not meant to be torn asunder. It has some of the poeticism of Sunrise and the pastoral imagery of The Southerner.

Still, ornery Mrs. Jessop vows to get in the middle of their marriage, and she does it quite handily. She signs her boy up for war — not out of any sacrificial heart and love of country — but purely out of selfish indignation. This act seems so egregious and totally indicative of her character.

What’s curious is how it is not so much dwelled upon as it becomes a reality in front of us. Perhaps her boy really wanted to go off to war and serve his country. We have some indication of that even as he only has a couple minutes with his betrothed before he ships out. It’s the first inclination that this is not about the lovers at all. Who does this event affect the most but Hannah herself?

It provides the needle in Hannah’s heart, and she has to live with her decision now for a lifetime. One of the film’s finest transitions comes with shots of enemy artillery caving in the trenches only to cut to a ferocious downpour at the Jessop farm. It’s two forms of chaos, one man-made and the other natural, but equally thunderous. In fact, the soundtrack is the same. They bleed into one another seamlessly.

Now the man we thought was one of our central characters is gone. It’s 10 years later and his mother is still there holding down her home. This might be when the lightbulb goes off. This was her story all along.

Soon a woman from the war department or some such organization shows up on her porch with the mayor to coax her to follow all the other Gold Star Mothers over to France bidding their sons one final tearful adieu. She surmises, “How reconciling it would be to stand beside the grave of one’s heroic death.” Of course, she’s doesn’t understand Hannah. It’s the bitterness and buried guilt still gnawing at her. She’s a proud woman, after all, and she’s adamant about not going. She very nearly doesn’t. However, if she never boarded that ship there would be no final act.

Ford’s sense of war is exhibited in how he’s able to cast it as both this swelling, deeply patriotic thing and still something troubling. He is aware of the dissonance of the horrors of war. The most touching sense of it all comes with a procession around a grave inlaid in the ground and the ladies all lay their flowers down on the grave, even Hannah.

True, they do the tour of the whole place and build a kind of maternalistic camaraderie touring around the Bastille, and Hannah and one of her newfound companions (Lucille La Verne) even tear up a local shooting gallery for kicks. It’s a sign of Ford’s penchant for broad humor, and he can never totally mask it.

But the subject feels different. For one thing, Henrietta Crossman’s performance feels like one for the ages and deeply impactful even today in a medium where stories of the elderly often feel dismissed or invalidated. In her time, she was a giant talent on the stage and you cannot watch the picture without gaining an appreciation for her.

Because this is about her evolution more than anything else — this is her story — and she carries it with the kind of aplomb that’s capable of moving mountains. By that, I mean the audience’s heart. We eye her watchfully for the majority of the film, and she’s righteously stubborn and outright vindictive in her jealous affections. Although it takes time, she melts, and this progression is key. It becomes evident within her very being.

The mode isn’t altogether subtle. She meets a boy on a bridge. Thoughts of suicide or something else might be swirling around in his half-drunken mind. She grabs him by the arm and by some force of compulsion takes charge of him. She feels a need to take care of him rather like with her own boy.

It’s true it’s a different actor and a different girl, but it becomes clear enough that they (Maurice Murphy and Heather Angel) are little different than her own boy and his girl a generation before. What has changed is her outlook. She sees their warmth, their fears, the hopelessly passionate affection they have for one another, and she sympathizes. Did she stop being a parent? Certainly not. Rather, her eyes have been opened just as she has been filled up with a far more benevolent spirit.

Finally, she comes to terms with being cruel. Finally, she realizes she had a convenient name for her attitude as “a God-fearing, hardworking, decent woman.” She talks some sense into another mother (Hedda Hopper of all people) in the straightforward manner she wished someone would have talked to her. It bears an incisive truth that’s hardly unloving. And it’s as if this is her slice of redemption because it is something we can see; Hannah sutures the wounds so they can heal. Both of another mother and her own.

She goes out to the Argonne somewhere and kneels before the grave of her son falling prostrate on it. For the first time, it feels she is actually able to grieve. It’s a cathartic release for a woman who has guarded her heart and buried her feelings and failures for years. What a glorious outpouring it is. All I could think of was that Pilgrimage has a sense of death Saving Private Ryan can never quite understand. The pain and relief of seeing this gravestone are so closely tied to our character. She is being made new in front of us.

There is only one thing left to do and as a final outward expression of her reconciliation and renewed heart, she reunites with the only family she has left on earth. Her estranged daughter-in-law and quizzical grandson. She overwhelms them and grabs her boy up in her arms. Because that’s what he is of course. Little Jimmy is a stand-in for his father and so Hannah smothers him with her love. It was a Pilgrimage to be sure. Hannah traveled across the sea only to come back home a revitalized human being. Now she can look into Jimmy’s eyes and know full-well she is forgiven and loved.

4.5/5 Stars