When you enter into the world of a film you often expect it to be perfect in your own minds-eye, following your own rationale to a logical conclusion. In that sense, Mystic River is invariably imperfect in how it ties up all its loose ends, but then again, what film really can bear that weight — and it’s all subjective anyhow. Instead, Clint Eastwood’s Boston-set drama builds off a story about three young boys and evolves into an engaging police procedural intertwining the lives and events of these three individuals. But it all starts with a game of street hockey.

When you enter into the world of a film you often expect it to be perfect in your own minds-eye, following your own rationale to a logical conclusion. In that sense, Mystic River is invariably imperfect in how it ties up all its loose ends, but then again, what film really can bear that weight — and it’s all subjective anyhow. Instead, Clint Eastwood’s Boston-set drama builds off a story about three young boys and evolves into an engaging police procedural intertwining the lives and events of these three individuals. But it all starts with a game of street hockey.

After losing their ball down a gutter drain, the three lads sign their names in a slab of wet cement, only to be accosted by a formidable man who won’t take their small act of defiance. He yells at the most unnerved of the three to pile into the backstreet of his tinted car. The boy thinks he’s off to the police station, but these men have far more traumatic intentions for him. It’s three days before young David flees into the woods like a spooked animal disappearing into the fog.

It’s a harrowing entry point of reference, that only makes sense after flashing forward to the present. The three boys are grown up. Dave, still hounded by his past, is married and raising his young son. Although work is hard to come by, they’re eking by.After a stint in prison and the death of his first wife, Jimmy is remarried, running a local convenience store. Sean is the straight-arrow of the bunch and became a cop.

As is the case with youth and childhood friendships, the ties that bind us together are often severed with the passing of time as people grow up and drift apart. But those formative years never leave us and when these three men are subsequently thrown back together, their past resurfaces.

One evening when Jimmy is in the backroom of his shop his daughter from his first marriage, the vivacious Katie gives him a goodnight kiss, as she is about to go out with friends. That same night Dave spies her partying at the local watering hole, but before he goes home he gets into an altercation with a mugger — at least that’s what he tells his wife. Except the next morning, Sean is assigned to a local crime scene along with his colleague (Laurence Fishburne), and it looks to be a grisly ordeal.

From thence forward, the seeds of doubt begin to spring up in our minds. What did Dave really do? Who killed this girl full of life and exuberance? Jimmy wants to know those exact same answers, and he’s welling up with bitterness and discontent. Sean walks this fine line of doing his duty and treading lightly on this man he used to know well and now is practically a stranger. Meanwhile, Dave lives his apathetic little life, looking to obfuscate what happened that night with the help of his fearful wife.

But of course, when Jimmy catches wind of what Dave did, he puts two and two together and comes to his own convenient conclusions. He wants justice after all. Even when Sean and Whitey make crucial discoveries of their own, it’s too late to stop the wheels from turning. Jimmy’s mind is already made up.

To his credit, Brian Helgeland’s script adeptly keeps all its arcs afloat, crisscrossing in such a way that leads to more and more questions, because there’s ever a hint of ambiguity. Nothing is quite spelled out and that’s paying respect to the viewer. However, there are moments where Mystic River enters unbelievable or even illogical territory, near its conclusion. Still, that does not take away from its overall strengths as a magnetic character study and gripping procedural. Tim Robbins and Sean Penn especially give stellar turns, the first as a frightened and mentally distressed man, the other as a hardened ex-con with vigilante tendencies. The fact that each character is grounded by their families is a crucial piece of the storyline, tying them all together.

4/5 Stars

WWII is always a fascinating touchstone of history because it has some many intricate facets extending from the Pacific to the European Theater to the American Home Front and so on, each bringing with it unique stories of everyday individuals doing extraordinary things. One of the best-kept secrets is the 442nd Infantry Division later joined with the 100th and effectively making the first all Japanese-American fighting unit which served over in Italy and France.

WWII is always a fascinating touchstone of history because it has some many intricate facets extending from the Pacific to the European Theater to the American Home Front and so on, each bringing with it unique stories of everyday individuals doing extraordinary things. One of the best-kept secrets is the 442nd Infantry Division later joined with the 100th and effectively making the first all Japanese-American fighting unit which served over in Italy and France. Contrary to popular belief, I wasn’t always a classic movie aficionado or a western lover but you do not have to be either of those to know and love the Duke because he is more of an American icon than a simple movie star in the conventional sense. He’s so integral to the very cultural fabric of our country. For instance, by watching I Love Lucy or M*A*S*H (and Radar’s impressions) or having one of your dad’s favorite film being True Grit, you can get to know him by simple osmosis. It’s just a fact. Even words like “Pilgrim” and “Baby Sister” begin to sneak into your everyday lexicon. You cannot help but hear them and by association use them (I’m not speaking from experience at all).

Contrary to popular belief, I wasn’t always a classic movie aficionado or a western lover but you do not have to be either of those to know and love the Duke because he is more of an American icon than a simple movie star in the conventional sense. He’s so integral to the very cultural fabric of our country. For instance, by watching I Love Lucy or M*A*S*H (and Radar’s impressions) or having one of your dad’s favorite film being True Grit, you can get to know him by simple osmosis. It’s just a fact. Even words like “Pilgrim” and “Baby Sister” begin to sneak into your everyday lexicon. You cannot help but hear them and by association use them (I’m not speaking from experience at all). But it’s from these roots that he ultimately moved out to sunny California, a noted member of the USC football team before a career-ending injury. This is a part of his life that I will mostly gloss over. Because it was the next part of his life that always resonated with me on a personal level. His very persona seems imprinted on the world that I grew up with from an early age. His name and likeness could seemingly be found everywhere. I grew up seeing his statue and even passing by his personal boat The Wild Goose and seafront home on family excursions (also featured in a Columbo episode).

But it’s from these roots that he ultimately moved out to sunny California, a noted member of the USC football team before a career-ending injury. This is a part of his life that I will mostly gloss over. Because it was the next part of his life that always resonated with me on a personal level. His very persona seems imprinted on the world that I grew up with from an early age. His name and likeness could seemingly be found everywhere. I grew up seeing his statue and even passing by his personal boat The Wild Goose and seafront home on family excursions (also featured in a Columbo episode). Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection.

Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection. At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey.

At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey. If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film.

If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film. You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams.

You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams. But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces.

But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces. Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact.

Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact. The opening notes of Joan Jett hollering “Bad Reputation” made me grow wistfully nostalgic for Freaks & Geeks reruns. The hope budded that maybe 10 Things I Hate About You would be the same tour de force narrative brimming with the same type of candor. It is not. Not at all. But that’s okay. It has its own amount of charms that forgive the obvious chinks in the armor of this very loose adaptation.

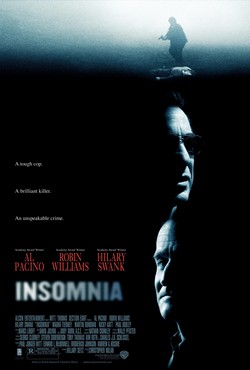

The opening notes of Joan Jett hollering “Bad Reputation” made me grow wistfully nostalgic for Freaks & Geeks reruns. The hope budded that maybe 10 Things I Hate About You would be the same tour de force narrative brimming with the same type of candor. It is not. Not at all. But that’s okay. It has its own amount of charms that forgive the obvious chinks in the armor of this very loose adaptation. “You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch

“You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch This was not the film I expected from the outset, and oftentimes that’s a far more gratifying experience. Nostalgia was expected and this film certainly has it, even to the point of casting the legendary funny man and cultural icon Don Knotts in the integral role as the television repairman.

This was not the film I expected from the outset, and oftentimes that’s a far more gratifying experience. Nostalgia was expected and this film certainly has it, even to the point of casting the legendary funny man and cultural icon Don Knotts in the integral role as the television repairman. One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.”

One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.” Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity.

Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity.