“Germany’s a pretty rough sea if you’re drifting.” – Breuer

“But I’m not alone anymore. There are so many drifters!” – Patricia Hollmann

Erich Maria Remarque is of course most famous for his work All Quiet on The Western Front, which was adapted to great effect for the silver screen by Lewis Milestone in 1930. Three Comrades, another one of his novels, feels very much like an extension of the same themes found in the earlier novel.

We find ourselves at the tail-end of the Great War. Mainland Europe is jaded and bedraggled. One must recall these were the days before Nazism: a force that felt like personified evil. When we look around from trench to no man’s land, it feels like everyone’s equally besmirched, equally implicated in the senseless killing.

So in this regard, it’s not a far stretch of the imagination to think a cohort of three German veterans might be likable to an American audience (especially because they are also Caucasian). However, equally importantly, they are played by three strapping young talents with charm bouncing off them like pinballs. It’s how they’re able to leave the calamitousness of war behind and attempt to discover a new life of humble contentment.

It was the war that instilled them with a certain collective memory, both scarring and then firmly solidifying their friendship in the aftermath. They take the world on like the Three Musketeers: all for one and one for all. Together they happily resolve to become car mechanics, carving out a peaceful existence for themselves, even as their beloved country has succumbed to a kind of mob rule with rampant new ideologies. To each his own.

Erich Lokhamp is the first, played by a dashing, if a bit wooden, Robert Taylor. Though it’s his friends who really seem to bring him alive. Franchot Tone is Otto Koster, always ready to support his friends and speak sense into their lives. His brand of loyalty is finer than gold. The other is Gottfried Lenz (Robert Young) also light-hearted while stricken with the mind of an idealist. Still, he gladly gives up his social conscience for the sake of his friends’ well-being. At least for a time, life is happy.

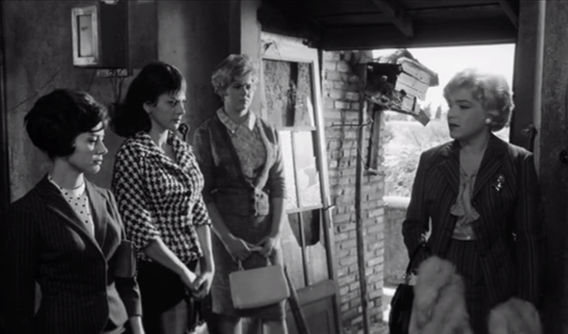

But before there’s any greater stakes, it begins as three lads having a blast taking a stuffy socialite (Lionel Atwill) for a ride as they roar down the thoroughfares in their beloved, hopped-up creation “Baby.” It’s a bit of good fun, but it also introduces the trio to one of the most important people in their subsequent life together: Pat

Margaret Sullavan is at it yet again a husky-voiced, troubled soul and yet overwhelmingly resolute in her pursuit of love and the preservation of those around her. It’s a quality found in all these characters — this self-sacrificial nature that becomes so laudable, if not entirely necessary. She is the one who surmises how lovely it might be to pick when we were born. Perhaps an age of reason and quiet. This sounds like a Borzage picture. Because of course, they must make do with the here and now, where evil still exists in the world (as it does in any era).

Their favorite hangout belongs to a jolly man named Alfons (Guy Kibbee). Erich takes his new girl there following some awkward interplay over the telephone. Also, his buddies always have a penchant for showing up uninvited to sit in on their evenings. It’s one of the added delights of the pictures because Young and Tone can supply the wisecracks to rib their friend.

I admire Otto and Gottfried even as I relate. They are faithful, they wish the best for their friends, act as encouragers — spurring each other on — and celebrating their victories while taking any setbacks as they always do: together.

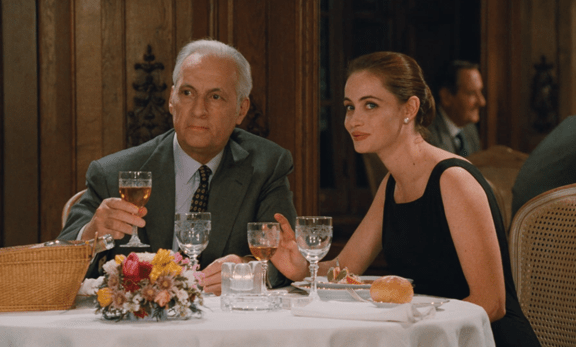

This courtship brings with it other complications, namely trying to impress a high society girl of culture no matter how good-natured she might make out. It’s still easy for a man used to the inside of cars, to feel out of place with the social elite, dancing and wearing customary uncomfortable clothing, which also has a habit of coming apart at the seams. He even spins tall tales of rolling down to South America, an exotic land full of monkeys and coffee, just so he might be able to keep up with her.

All of this show proves unnecessary. This is how it works when you are smitten with a rich man’s girl and, more importantly, when she is in love with you. In another line that feels transcendent in the usual manner of Borzage, they aspire to being “lovers on the edge of eternity between day and night.”

A lesser film — or at least one ill-befitting the predilections of Borzage — would probably have made this a fight for the woman’s hand. It’s easy enough to see how this would have pulled the boys’ bond asunder. And yet these characters are more genial, enlightened, and well-intentioned. The story itself strives for something more. Young plays cupid urging his friend toward marriage. Tone’s character knocks out a concerto on their automobile as he tries to hammer away some sense into Pat in favor of his friend.

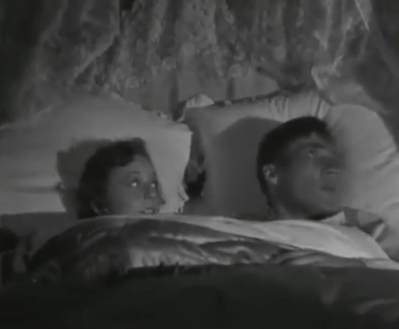

Propitiously, all this coaxing culminates in the quaintest wedding, which somehow fits all the players to a tee. Borzage captures it such that we feel we are there with them discovering it as it happens, partially spur of the moment, but also imbued with this star-crossed purposefulness. In step with everything else, their honeymoon to the seaside is as gay as can be until it is met with a setback.

It plays into the film that Sullavan always feels emotionally strong and sturdy but often physically frail. Maybe she just exudes this quality between her throaty vocals grasping at words and the obdurance she gained a reputation for. But in Three Comrades, she is bedridden and in critical condition from hemorrhages — still nursing sickness that has clung to her for some time. Erich has little idea, but once again, Otto comes to their aid with his usual expediency. It only serves to bring them together.

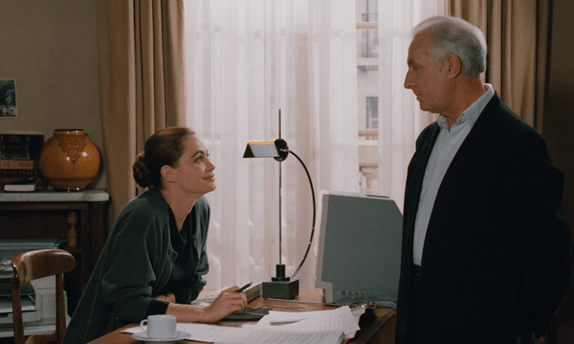

While remaining unnamed throughout the film, there’s little question that the rising Nazi Party is the instigator of public brawls. Dr. Becker (Henry Hull) speaks out on his soapbox about the need for reason in confronting the issues of the times, instead of the prevailing violence. Since it’s not the first scuffle or an isolated event, Gottfried feels compelled to stand up for his beliefs, putting his ideals on the line.

Meanwhile, Erich has a less politically charged fistfight in the streets over a work claim. He gets ganged up on before his comrades, of course, fly to his defense. Just like old times. Pat is placed in a sanitarium on the behest of her doctor (Monty Wooley) just in time for the snows of winter and then Christmas.

The violence continues to escalate, this time dragging Tone into a shootout in the streets with Handel’s “Hallelujah” clamoring in the background. It’s oddly hypnotic even as it spells what feels like the end of the beginning.

If it’s not apparent already where Three Comrades is going, it easily functions as a fitting companion piece to Borzage’s later Mortal Storm because there is this same uncanny prescience about it, although it probably did very little to halt the impending course of history. The unholy mechanisms were already in place.

Every Borzage movie makes the world a little broader and love a little grander to match. In this regard, the meeting of the prose of Erich Maria Remarque and F. Scott Fitzgerald somehow manages to work in the hands of a director.

What sets it apart from a melodrama like Douglas Sirk’s is the slow burn and how the characters take each moment on with their own brand of quiet fortitude. In many ways, love (and camaraderie) are an antidote to the wiles of the world. Our heroes know what’s inevitable and they brave it together — smiling until the end of days — even in the face of tragedy and hardship.

Is it high-minded and idealistic? Most assuredly. But it’s also one of the most blessed hallmarks of Frank Borzage’s filmmaking. This hallmark, more than anything, is why we can easily draw a line in the snow from something like Seventh Heaven or Man’s Castle to Three Comrades and then The Mortal Storm.

One is especially reminded of Margaret Sullavan because one of the pervading attributes of her characters is this all-encompassing dignity to see her to the end. We feel like unsightly sots and indignant peons compared to her eminent calm.

But really, the same might be said about all the players in Three Comrades. It’s a pacifist portrait. Not so much in prognostications of any sort. It has to do with the inner peace inside the characters that radiate out from them, due to their affections for one another. Thus, in a fitting Epilogue, with fighting breaking out in the city, the four inseparable friends walk off solemnly together. If not in body, then certainly in spirit.

4/5 Stars