“Photography is truth, and cinema is truth 24 times a second.”

Although Le Petit Soldat was released in 1963 — no thanks to the censors — it was actually filmed in 1960. This context is all-important because Jean-Luc Godard is still fresh off the sensibilities of Breathless, and they pervade this film as well.

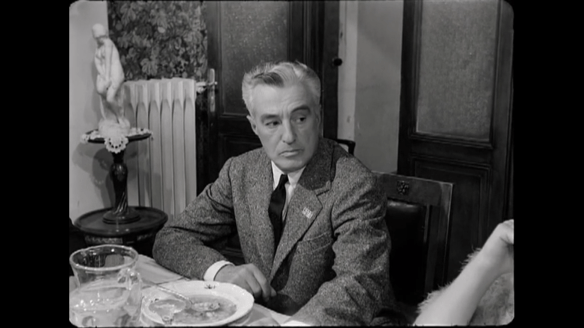

Its plot follows the aftermath of a professor killed in a terrorist attack and a young journalist in Geneva, who is enlisted by French intelligence to assassinate a man named Palivoda. This is in the age of the Algerian War; the young man, Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor), has avoided the draft, and the man he’s assigned to kill is a National Liberation Front sympathizer.

If it’s not apparent already, the groundwork has been set for a political spy thriller. While balking at murdering the man in a drive by, Bruno simultaneously falls in love with Veronica (Anna Karina), a dark-haired beauty in a trench coat. His friends bet him he’ll fall in love the first time he sees her on the street. He sheepishly shells over the money after only a brief introduction. He’s instantly smitten.

Le Petit Soldat is such a literary film thanks in part to its voiceover. Bruno, as Godard’s stand-in and cinematic conduit, references a myriad of things. He asks rhetorically about Veronica, “Were her eyes Velasquez gray or Renoir gray?”

It’s as if Godard is contemplating the muse in his own art. Still, he continues with a steady stream of namedrops including painters, authors, and composers. Van Gogh and Gauguin. Then, Beethoven and Mozart. Anna Karina prancing around to Joseph Haydn is definitely its own mood.

It occurs to me this is a distillation of Godard as a filmmaker. It’s a visual style wedded with these deeply mined traditions of literature and art. Both cutting edge and steeped in the culture of the past before thenceforward going off and creating its own unique vocabulary.

Godard gleefully inserts himself all over the movie on multiple occasions where we see him in the flesh. It’s a spy movie as only he can conceive it totally deconstructed and aware of itself while simultaneously taking most of the thrills out of the genre.

Soldat remains a precursor to Alphaville by effectively turning the contemporary world around him into the environment for his latest genre picture. Whereas Breathless‘s jazz-infused contemporary aesthetic is accentuated by the black and white streets of France, here they are repurposed. Though it’s as much a film about driving around the city philosophizing as it is about any specific dramatic action.

Because Francois Truffaut, while not always disciplined, could spin stories with a narrative arc and genuine emotion. Godard is at his best as a philosopher and cinema iconoclast where his style doesn’t totally get bogged down by ideas, and he uses the medium in ways that would become the new standard. Or at least his own standard, before he decided to upend them again.

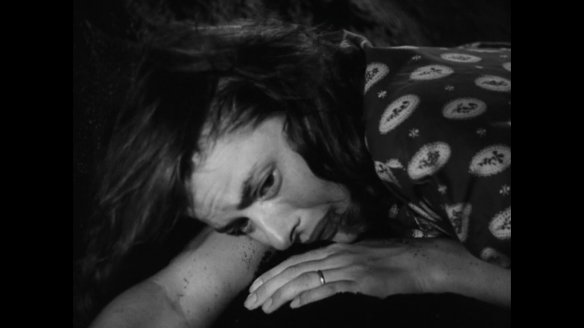

But in order to make the case for Anna Karina as more than Godard’s Pygmalion, it’s necessary to consider her screen image in depth. Whatever Godard gave to Anna Karina in terms of iconography or legacy, Karina gave that much back, and they will be inextricably linked for all times. Because if there was ever a reason to fall in love with her, it’s right there in Le Petit Soldat.

His alter ego riffs about God and politics, political left and right, quotes Lenin, and unravels his entire worldview (ie. about a man who loves ideas, not territories). When he asks his girl why she loves him, she shrugs her shoulders and says I don’t know. I don’t think she’s dumb, but whereas here we have one character who is in their head, she seems to be a creature who is real and present in the moment. She has a heart.

Whatever the digressions and despite the perplexing way Bruno interrogates her during their impromptu photoshoot, she is undeniable. If cinema is truth 24 frames a second, she somehow makes Godard’s cinema more accessible and real — she takes his theorizing on truth and gives it a pulse.

The movie is still a thriller, and it follows its own version of narrative beats. Bruno is framed, he continually has second thoughts about his assignment; he gets the gun, but things always get in his way. His heart is not in it — killing a man mercilessly — because this is not who he is.

Instead, he wishes to run away to Brazil with his girl. He’s locked away and tortured as a double agent for his troubles. These sequences are simplistic — contained in a hotel bathroom — and yet as they light matches near his fingertips and dunk him for minutes on end in the water, there’s a definite heartless menace about it.

We have the political bent of Godard’s cinema detected early on before his other overt efforts later in the 60s. It comes in the guise of his story as it unpacks current events, ideologies, and even controversy around torture.

True to form, he has the audacity to cram the final act of an entire movie into one minute of celluloid. He shows us some things and just as easily explains away the rest with voiceover.

It feels like he leaves just as he emerged. He’s totally singular. At times, maddening and bombastic, and yet always prepared with his own take and alternative approaches to convention. Godard will always challenge the viewer and make you reconsider how much you appreciate cinema even as he continually helps to redefine how we conceive things.

1960 or 63. It makes no difference. Le Petit Soldat has a young man’s malaise acting as a film for the coagulating disillusionment of the ’60s. This isn’t your father’s war nor one of his films — not the “cinema du papa” as Truffaut put it. If Godard’s style was coming into its own, with Karina cast front and center, then the propagation of his ideas is equally evident. Cinema would not be the same without his distinct point of view.

3.5/5 Stars

Note: This review was written before the passing of Jean-Luc Godard on September 13, 2022.