“Paisan” feels like a ubiquitous term. At the very least, it seems to have entered into a shared vernacular most Americans understand. And of course, this is part of the reason Roberto Rosselini’s follow-up to Rome Open City employs the word.

His newfound audience would be able to appreciate its very simple meaning with some amount of recognition. But it hardly seems like a ploy because it illustrates the core themes of the picture. And this is not done through an epic narrative stretched out over a couple hours time. It is built out of these mini-scenarios coming to represent a breadth of WWII experience between Italians and Americans.

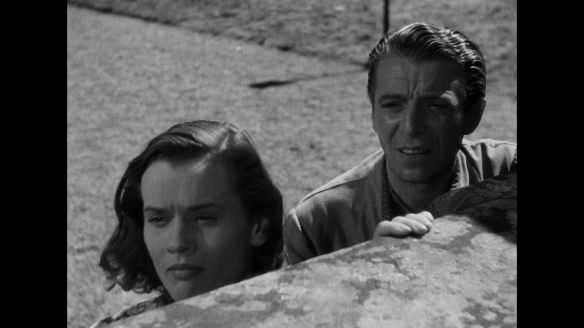

We open in 1943 in Sicily with a group of American soldiers making their way through the villages for recon. As has a habit of happening in these cross-cultural pictures, the English language sounds like tin to the ear, but when they meet our first Italian characters and the dialogue is interspersed, we immediately get something richer and more intriguing because we have both languages dancing off one another and fighting for some primacy over the scenes.

Much of the movie is negotiated in these spaces in-between what is understood and what must be inferred and left only to the imagination. The benefit of subtitles gives us a privileged position, but not all of these characters have the same luxury.

Even when one soldier is called upon to keep watch over their guide in the caves — a young Italian girl looking for her family — we settle on something so basic. It’s their lack of communication and it can invoke fear and conflict, but it can also remind us of our most basic commonalities.

Conversation about cows and milk progress as the soldier reminisces about his family back home in photos. This pleasant interchange is really only a momentary flame, quickly snuffed out. Because we are reminded there is a war at hand and conflict comes from the outside and kills their moment together.

Before we are left to dwell too much on the present, we march ever onward toward Naples. Here is a tale we might see from De Sica and later in Germany Year Zero. It’s a story of youthful vagrants — one named Pasquale — who lives on the streets buzzing around G.I.s like a misquito looking to suck them dry out of pure necessity. It’s an extraordinary scene to watch the young boy latch onto a drunken black MP (Dots Johnson).

Their saga drags them all across town and, again, they hold two-sided conversations that are totally at odds with one another. As they sit on a pile of rumble together, it strikes me how this little boy sees the man for what he has. Yes, he’s black, but he’s American, and what a privilege that is. He runs off with his boots with a kind of fatalistic inevitability and that could be the end of it.

Instead, they meet again in another chance encounter. The soldier seeks restitution and yet Joe’s attempt to get back his stolen property feels almost inconsequential when he recognizes the desolation around him. This disparity is especially complicated when you put it next to the hypocrisy of racial discrimination back home.

He represents wealth and prosperity and still must feel some relegation to second-class citizenship in his own right. In 1946 Harry Truman had yet to integrate the military and, at best, even this felt like a symbolic victory at best.

The way Paisan links together these individual studies in character and relationship means the movie offers up this extraordinary breadth while still maintaining a hypersensitive level of intimacy. Because it takes a single interaction between disparate people and allows them to play out in such a way they come to represent something so much broader.

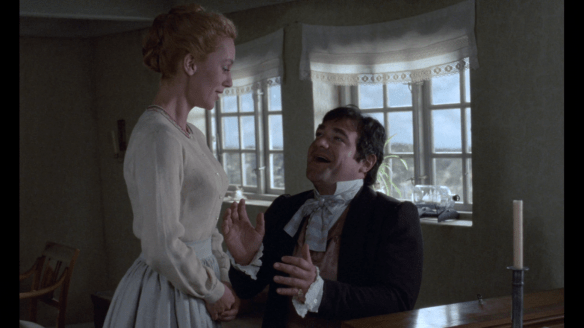

Later, it’s June, 1944. There’s a voice in the darkness shouting about American cigarettes ready to smoke. Glen Miller’s “In The Mood” is instant shorthand, and it coincides with a dance hall packed with folks. This is a new Rome from the one in Rosselini’s original film, until the military police soon shake up the joint and send the locals into a tizzy.

A fugitive in furs (Maria Michi) evades the authorities and picks up a soldier boy (Gar Moore) on the street over cigarettes. Remember, this is the era of Now Voyager and Bogey and Bacall. They are the cultural tastemakers. It’s a portrait of how even a short span of time — 6 months — can change people drastically, where the hopeful optimism and jubilation of the liberation can quickly be displaced with rowdy opportunism and disillusionment. And with it, a final reunion is precluded in a turn of events that might as well be anticipating the wistful fates of Jacques Demy over 15 years later.

The movie continues in Florence along the Arno River. Here a young Allied nurse (Harriet Medin), who knows the area intimately from time abroad, sets off on a singular mission to find an artisan friend, who is currently in the midst of the local skirmishes. The streets are full of firefights playing out in unsentimental terms.

In one way it feels ludicrous watching this woman and a fellow searcher streaking through the treacherous zones of no-man’s-land, and yet we cannot turn away. In a Hitchcock movie, we might term the arbitrary goal they are pursuing the Macguffin. It makes no difference.

I’ve come to realize that Italian Neorealism has come to signify a kind of emotional truth paired with authentic visuals. It’s not documentary, but it takes the layers and contours of the real world to tell what feels like mini tragedies wrapped up in these individual segments.

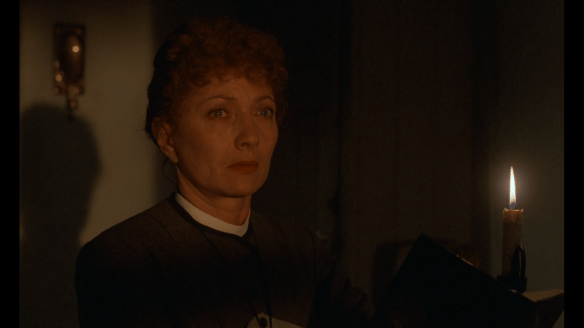

Paisan keeps on offering up these nuggets that intrigue me. I think of the next story, which feels like a more peaceful, mundane tale about three American chaplains who rest at the local monastery. There’s so much benevolence even as we are reminded the vocation they follow is unified the world over.

One of the visitors tells his peer, “I think one can really be at peace with the Lord without removing themselves from the world. After all, it was created for us. The world is our parish.” These words feel like they come straight from Martin Luther, a man who looked to democratize the Christian faith and break any vocational dichotomies.

Sure enough, he’s a Protestant and another man is a Jew. This revelation causes a wave of worry to come over the local Holy Men. Surely these guests are lost. They have not found the path because their beliefs are marred by inaccuracies and flaws (possibly even heresy). Rather than digging into this spiritual discourse, it settles for a kind of moral stability, not quite an inclusive gospel but certainly a call for tolerance and appreciation across the religious ranks.

In the final chapter, Italian Partisans and American OSS fight a desperate guerilla war against the impending Germans. It’s not a chapter of history we consider in detail, but we are placed in the moment so we forcibly comprehend the exhausting futility of their tactical battles. They live day to day constantly striving to stay out of reach of a tireless enemy. The only thing keeping them alive is their fierce camaraderie. They fight for something larger than themselves.

The ending of Paisan is matter-of-fact even as the imagery is bleak, and it feels like a callback to the opening story. We are reminded of the utter inhumanity of war, but Paisan was obviously meant to be used as a tool of mutual healing between the U.S. and Italy. Because it’s the humanity bleeding out of the movie coming to the fore, more than any amount of tragedy.

4.5/5 Stars