As an American, the history of Apartheid is still something I feel relatively ignorant of even as I must confess to still be learning constantly about our own history of segregation in the U.S. This is part of what makes me marvel at Cry The Beloved Country, which really is one of a kind — a bit of a gem plucked out of the 1950s.

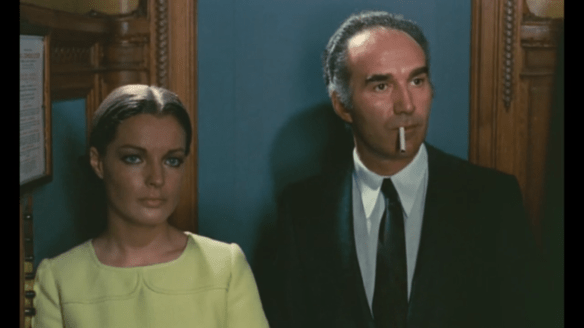

Because the talents are innumerable, a young Sidney Poitier on the rise and Canada Lee in what would turn out to be his final screen role. I haven’t seen many of them, but this might be his best. Because although there is plenty of time to speak of Poitier for any number of movies, well worth our time and consideration, this particular film is carried first and foremost by Lee.

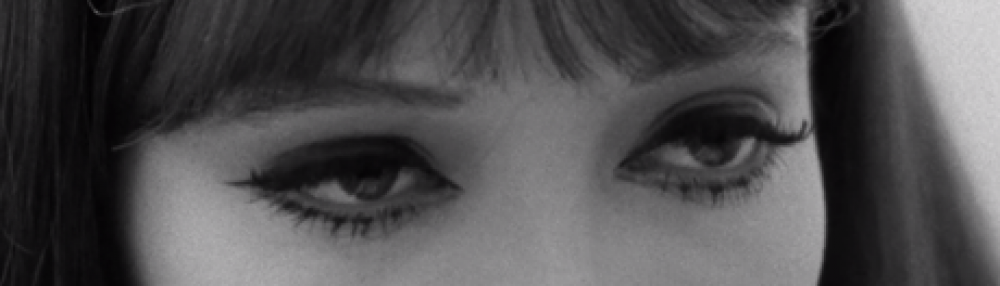

It impresses upon us a certain dignity of spirit. He’s a priest named Kumalo, stately and compassionate in all aspects. His eyes bear the same melancholy of a man who has been forced live under the weight of many hardships. It also makes us yearn that his stage efforts might have been captured for posterity as he famously worked with a theatrical wunderkind in Orson Welles and built up quite a career for himself. Alas, this was not to be.

One must confess that the reason for his starring turn was partially out of necessity. American, now deep in the throes of the Red Scare, was no friend to him or anyone who purportedly had Communist connections, whether real or imagined. The fact that he was black definitely didn’t help matters (Just ask Paul Robeson).

Meanwhile, Sidney Poitier was on the entirely opposite end of his career: Now in his early 20s and coming from the stage to navigate the strictures of Hollywood set before him. He’s so young, but he holds a civility and a stature that make him feel fully present and somehow wise beyond his years. This would be a trend throughout his lifetime.

If it’s not evident already, Alan Paton’s 1948 novel is totally engaged with the contemporary issues of South Africa, ranging from systemic racism to pervasive poverty. If they are contextualized to this culture, surely we aren’t ignorant enough to believe they have no bearing on our own historical background.

So here we are in South Africa offered an auspicious film by Zoltan Korda meant to be about something of real consequence — to speak of the ills and indiscretions of society — when we purposely build structures of oppression. The production is steeped in its share of legends, the most famous one being Korda pronouncing Lee and Poitier as his manservants so he could get them into the country to film. If nothing else, it adds not only to the aura but also the concrete reality of what is in front of us.

For a black man, Johannesburg feels very much like the valley of the shadow of death. When Reverend Stephen Kumalo (Lee) receives a letter, it sends word that his sister is ill. His mission is twofold: support his ailing sibling and track down his son Absalom.

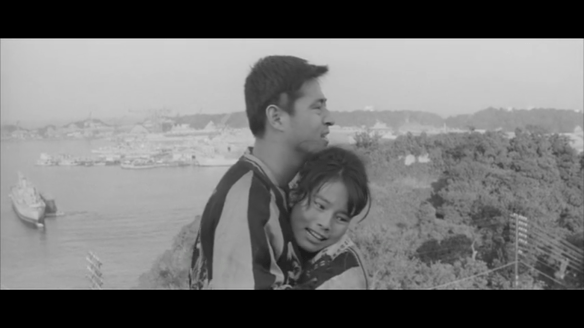

In many ways, Cry, The Beloved Country is a journey film as one man pursues answers and then restitution for a life. I wouldn’t say all the performances feel natural, but at the center of the drama Lee and Poitier act as a bit of an anchor for the entire movie. We have them to cling to. And even if the local, untrained performers leave something to be desired in terms of emotional resonance, the milieu around them speaks volumes.

There is an austere veracity that’s innate to on-location shooting. You could not possibly achieve this kind of atmosphere any other way. The overall degradation and the poverty are palpable in most every frame filled with the blocks of shantytowns.

It also willfully engages with issues of black-on-white crime. In a society whose social structures and racial castes are tenuous at best, these are perilous waters to breach. The newspaper headlines detailing a botched robbery are made far worse by their immediacy.

The man killed was an idealistic reformer envisioning a world of greater equality and stability for the black community. This show of brutality against someone sympathetic to their plight is poor P.R. nor does it placate his crusty old father (Charles Carson), who never believed much in his crusading, to begin with. For people of his age and estate, white is white, black is black, and never the twain shall meet. It’s not to say evolution is not possible…Between the frail sympathies of his wife (Joyce Carey), looking at his late son’s writings, and a fateful encounter, there’s still room for ample growth.

However, this crime also has bearing on Stephen as well. Because his boy Absalom is one of the men implicated in the killing. It’s a father’s worst nightmare, and he’s powerless to prevent it. Here two fathers are juxtaposed while coping with two strains of unfathomable grief.

Soon court dates are set, and there’s a trial for the murder of young Jarvis and the impending deliberations. Although all the elements are there, the plotting and execution never add up to anything that feels more than intermittently affecting. It’s the kind of film I like the idea of it and what it stands for rather than what it actually culminates to onscreen.

Make no mistake. Cry, the Beloved Country feels like imperative viewing if we want to understand what empathy is in the face of our own limitations and human biases. To my knowledge, it’s nearly an unprecedented historical documentation granting center stage to black actors who deserved more acclaim. And thus, our attention must consider and appreciate the performances.

For Poitier, in a fledgling career, there would be still so much ahead of him. For Canada Lee, an unfairly forgotten talent now, it was the end. He would go the way of his buddy John Garfield and many others, perishing no thanks to the toxic industry around him. Cry, The Beloved Country is not a great movie, but it’s an understated one, brimming with solemnity, and sometimes we would do well to have this posture. We can mourn our own sins, the sins perpetrated against us, and the sobering reality that the world is not as it should be.

3/5 Stars

Note: This review was originally written before the passing of Sidney Poitier on January 6, 2022