Doris Dowling has a name that sticks out in the opening credits for the very reason she was an American actress and she offered up a particularly memorable role as Alan Ladd’s vitriolic wife in The Blue Dahlia. Here she’s an Italian playing the moll of a two-bit hoodlum wanted by the police.

Bitter Rice opens with a curious kind of introduction. A man stares straight at the camera, breaking the unwritten contours of the fourth wall while providing some explanation of how rice harvesting is a bumper crop not only in China and India but in Northern Italy as well. A moment later, the camera pulls away revealing this presentation is all part of Radio Turin and suddenly the circumstances of the film are instantly placed in a palpable setting.

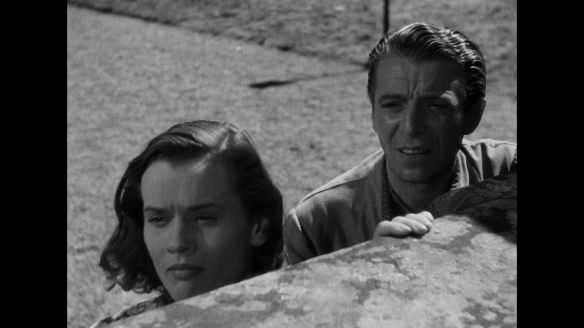

The lithe even upbeat nature of the picture allows us to fall into the world almost immediately. We have a milieu of migrant workers crossed with bustling train stations, lovers, policemen, and wanted fugitives all playing out in front of us as we try to take in the stimuli and come to grips with everything. The wanted man, named Walter (Vittorio Gassman), tries to mask himself by dancing with a pretty young field worker (Silvana Mangano). She gladly flaunts her dancing in exchange for attention as she’s accompanied by her portable gramophone.

In the aftermath of a chase, Francessca (Dowling) disappears into the crowd of workers to lay low with their cache while her boyfriend flees in order to stay out of the clutches of the police. If it’s not apparent already, a passing street vendor lets us know some priceless jewels were stolen from The Grand Hotel.

If it’s not apparent already, this opening gambit has the kind of thrust we might expect from Hollywood, not a backcountry Italian film, and it’s evident Giuseppe De Santis is well aware of the mechanisms of a thriller. However, he also allows his picture to sink back into rhythms that one would feel much more accustomed to with neorealism and a movie set in the province of Vercelli.

Suddenly a tale of illegals and registered workers is given a new context but timeless relevance to this very day. Francesca does not have a license, but she befriends the saucy young dancer, Silvana, who does her best to assuage the foremen and get her new companion on the ever-crucial list of approval. Her chances are tenuous at best, but Francesca, like so many others, has no other choice.

I couldn’t help thinking, with her chewing gum and sizzling hot music, Silvana is bred out of the same world that supplied movie posters of Gilda in Bicycle Thieves. It’s this influx of American product in its many modes — a new form of cultural dominance — steamrolling the former fascism into submission to good ol’ American capitalism.

The way she flaunts herself and becomes the focal point of the picture, I couldn’t help but compare her to Virginia Mayo in some of her saucier roles like Best Years of Our Lives or White Heat — down to the gum chewing. If it were an American film, Bitter Rice would fit somewhere within the landscape of The Grapes of Wrath or maybe Border Incident.

There’s little doubt it has a kind of collective political philosophy to present — its own vein of social commentary — and it delivers it not only through narrative, but visual depictions of the life these people are subjected to.

In one breathless comment, Silvana tells a soldier (Raf Vallone) posted nearby, “In North America everything is electric!” He’s informed enough to know “even the chair is electric…” As a side note, the Italian constitution completely abolished the death penalty for all common and civil crimes starting in 1948. Already it presents a kind of ideological chafing that must be contended with.

Upon their arrival, the rice workers receive a hero’s welcome, and we are reminded this is a yearly ritual with its own unique patterns. There’s something marvelous about taking part in these seemingly familiar habits even as we see them for the first time as an audience.

The packing of mattresses with straw, the throwing of hats to all the field hands who catch them out of the air en masse. It’s strangely riveting. Or there are the mating customs played out year after year with men yelling over the wall to the fair maidens below, searching for former flings and future partners.

We come to realize it’s built on its own kind of ecosystem. You have the foreman’s, the lines of workers bent over in the muck and the mire every which way, and they sing their river ballads to pass news along the line.

With the jewels to get between them, Francesca and Silvana find themselves positioned among the two factions of documented and undocumented workers. It’s not a simple task, and then Walter turns up again. He can only bring trouble.

Like their opening foray, there’s something about the dance scene between Silvana and Walter burning with a palpable sensuality. But what it also does quite effectively is pluck the film out of its neorealist roots and make it even momentarily something more. It’s like a precursor to the passionate sashaying in Picnic. It feels like very much a Hollywood creation and yet it’s simply De Santis’s version of it.

Likewise, the film is not totally averse to forging its own version of a love triangle (or diamond) with Francesca and Silvana finding themselves attracted and repelled by the conman Walter and another character, the soldier Marco. These see-sawing relational dynamics are the fodder for unadulterated melodrama exemplified by violent pursuits in the pouring rain, passionate embraces in mountains of rice, and a great deal more.

While the rest of the harvesters get overtaken with merriment in the wake of a wedding and subsequent beauty contest, there’s something much more catastrophic going on in the background. Silvana becomes the self-destructive queen of it all.

By the end, I stand totally astounded. Bitter Rice jumps off the deep end going from Italian Neorealism toward gut-busting, blistering drama with the dark tinges of noir. This is what it borrows from Hollywood quite effectively, reminiscent of a picture like Border Incident or even Cape Fear. In tight quarters, violence becomes especially animalistic. When a beast feels cornered, he must lash out.

Also, I still am fascinated to know why Doris Dowling was cast in a film that was otherwise completely Italian, and yet there’s something rather ironic and bewitching in her and Magnano becoming cultural foils for one another. It becomes a far more complicated portrait of the corrupting forces of greed and capitalism.

Dowling, as the quintessential, steadfast Italian girl, and the Italian actress as a poisoned vessel of sensual pop culture materialism. What’s more, it leaves a truly incisive impression and that’s most important of all. You won’t soon forget a film like this, and it just might have the power to captivate viewers on both sides of the globe with its pulpy sensibilities.

4.5/5 Stars