Despite my general reluctance to say that the Western in its classical form was on the way out, it’s hard not to make such an assertion looking at the landscape of the late 1960s. The Wild Bunch is a common marker of the seismic shift leading to the complete obliteration of the classic western mythology, but there are some related themes strewn throughout Butch Cassidy that make it equally representative of an era or so one could argue.

The times were changing historically speaking and that plays out cinematically in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Bicycles are the future, destined to replace the old reliable horse. And the western hero as we knew him has long since gone, replaced instead by vengeful tough guys and in this case a pair of bank robbing antiheroes. Bonnie and Clyde were the new standards and out of that trend, we saw more like them.

So it’s not just the fact that the film takes place at the tail end of the Old West, slowly evolving into the modern, or New West, but simultaneously the genre would never be the same. There’s a bit of a wistfulness to it all. The legend is fun. The mythology is something to be thoroughly embellished, but it too comes to an end. It’s only a wisp of a memory made of sepia tones and silent newsreels. But Butch Cassidy and Sundance will be remembered fondly by the audience just as the West is. Maybe that is enough.

Unfortunately, Butch Cassidy as a film does have its shortcoming which became more apparent with time. It’s possible to be a dated period piece as this film is (although it’s hard not to love “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head). Still, it can be plodding and some would argue it’s about nothing substantial, nothing meaningful at all. Still, it manages to be one of the greatest western comedies of all time only eclipsed by its own heavy dose of cynicism.

It’s funny watching Butch and Sundance go through their motions. Butch (Paul Newman) is the brains who bemoans the fact that banks are getting upgrades and shipments are being made by trains. After all, they are constantly on the move and it becomes a constant guessing game. He’s given more grief by his gang that looks to overthrow him led by the hulking thug Harvey (Ted Cassidy).

And on top of that every lawman wants him dead. In such moments, being the idea man that he is he entertains thoughts of joining the army for the Spanish-American War or even going to a far off land like Bolivia. Content with his gunplay and letting Butch do the thinking, Sundance rides by his side, certainly his own man but also part of this comic duo.

William Goldman’s script is brimming with wry wit that’s almost inexhaustible. But Paul Newman and Robert Redford loom even larger as the titular stars in this epic buddy comedy. In the age where winning charm and star power still seemed like a genuine box office draw. You came to see actors and in 1969 there were few actors as commanding as Newman and Redford. They had looks and charm. Cool and comedy. Charisma goes a long way. For those very reasons it’s an impressive film and enduringly entertaining. If we cannot watch a film and enjoy it as pure entertainment at least on some level, it really is a shame because that’s one of the many joys of the cinema.

But there’s also something admittedly depressing in how their story evolves. It can no longer be about snide repartee and living the good life robbing banks, continuously augmenting their legendary notoriety. It’s light and funny for a time before slowly spiraling into a deadly cycle.

Perhaps my faith in Butch and Sundance wavered slightly but I will go on resolutely and maintain my immense affection for them that began as a boy. This is still a wonderful film. Outlaws do not have to be one-dimensional. They can be just as funny as they are depressing. That is their right and the legend of the Hole in the Wall Gang is exactly that type of story. We don’t have to see them die. Instead, we get the satisfaction to leave them in one last shining moment of triumph. One final triumph of the West as we once knew it.

5/5 Stars

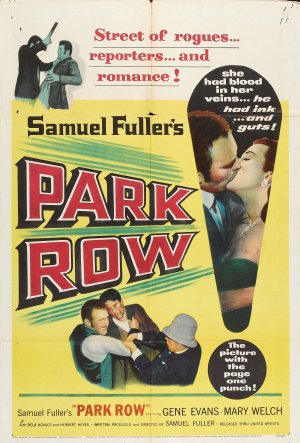

It’s no secret that Sam Fuller cut his teeth in the journalism trade at the ripe young age of 18 (give or take a year) and so Park Row is not just another delicious B picture from one of the best, it’s a passion project memorializing the trade that he revered so dearly.

It’s no secret that Sam Fuller cut his teeth in the journalism trade at the ripe young age of 18 (give or take a year) and so Park Row is not just another delicious B picture from one of the best, it’s a passion project memorializing the trade that he revered so dearly.

Initially, I Remember Mama comes off underwhelmingly. It’s overlong, there’s little conflict, and some of the things the story spends time teasing out seem odd and inconsequential at best. Still, within that framework is a narrative that manages to be rewarding for its utter sincerity in depicting the life of one family–a family that feels foreign in some ways and oh so relatable in many others.

Initially, I Remember Mama comes off underwhelmingly. It’s overlong, there’s little conflict, and some of the things the story spends time teasing out seem odd and inconsequential at best. Still, within that framework is a narrative that manages to be rewarding for its utter sincerity in depicting the life of one family–a family that feels foreign in some ways and oh so relatable in many others. Upon being thrown headlong into Christopher Nolan’s immersive wartime drama Dunkirk, it becomes obvious that it is hardly a narrative film like any of the director’s previous efforts because it has a singular objective set out.

Upon being thrown headlong into Christopher Nolan’s immersive wartime drama Dunkirk, it becomes obvious that it is hardly a narrative film like any of the director’s previous efforts because it has a singular objective set out. Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.

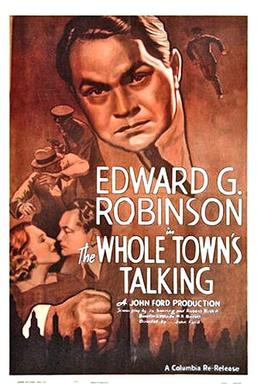

Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it. Comic mayhem was always supercharged in the films of the 1930s because the buzz is palpable, the actors are always endowed with certain oddities, and the corkscrew plotlines run rampant with absurdities of their own. Penned by a pair of titans in Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking opens with an inciting incident that’s a true comedic conundrum.

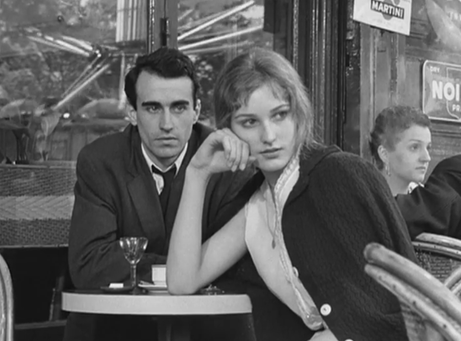

Comic mayhem was always supercharged in the films of the 1930s because the buzz is palpable, the actors are always endowed with certain oddities, and the corkscrew plotlines run rampant with absurdities of their own. Penned by a pair of titans in Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking opens with an inciting incident that’s a true comedic conundrum. Pickpocket is an intricately staged, truly intimate character study from the inimitable Robert Bresson solidifying itself as one of his greatest works. As was his practice, Bresson took Martin LaSalle, a non-actor to be his leading protagonist.

Pickpocket is an intricately staged, truly intimate character study from the inimitable Robert Bresson solidifying itself as one of his greatest works. As was his practice, Bresson took Martin LaSalle, a non-actor to be his leading protagonist.

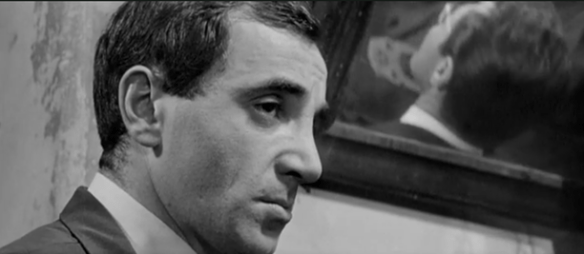

The opening credits of Vivre sa Vie commence with the opening note “dedicated to B-movies” and indeed many of Jean-Luc Godard’s best films could make the same claim. They’re smalltime stories about little people living rather pathetic lives if you wish to be brutally honest. This isn’t Hollywood.

The opening credits of Vivre sa Vie commence with the opening note “dedicated to B-movies” and indeed many of Jean-Luc Godard’s best films could make the same claim. They’re smalltime stories about little people living rather pathetic lives if you wish to be brutally honest. This isn’t Hollywood.