Soldiers returning home from war is a recurring theme in films such as The Best Years of Our Lives and Act of Violence and given the circumstances it makes sense. This was the reality. Men returning home from war as heroes. But even heroes have to re-acclimate to the world they left behind.

Soldiers returning home from war is a recurring theme in films such as The Best Years of Our Lives and Act of Violence and given the circumstances it makes sense. This was the reality. Men returning home from war as heroes. But even heroes have to re-acclimate to the world they left behind.

Blue Dahlia is not so much about the assimilation of G.I.s though. It’s more an excuse to show the noir world creeping into a man’s life infecting all he left behind. As he returns, Johnny Morrison’s wife (Doris Dowling) is keeping company with another fellow (Howard Da Silva) and everyone else seems to know about it except Johnny. Also, his young boy died tragically while he was away and his wife has taken to a life of drinking and partying. He’s not expecting any of this but then again what happens in film-noir is very rarely what we expect.

Raymond Chandler weaves together his first original screenplay here, a production that was hampered by the impending deployment of Alan Ladd as well as Chandler’s own bouts with alcoholism and writer’s block. It’s hard to know which one caused the other. But either way, the film finds its roots in a murder and the man who is suspect just happens to be the returning G.I. Before he ever knew people were looking for him he playfully took the name Jimmy Moore after meeting a lady (Veronica Lake) who happens to be closer to him than either of them realize. Their paths cross more than once.Then he’s on the run. His war buddies (Hugh Beaumont and William Bendix) are worried about him after being questioned by the cops. And the cops are anxious to hone in on the killer because no one is of any real help. No solid leads come their way and that means Johnny has to track down the killer himself.

The direction of George Marshall is not particularly inspired but his players are compelling enough. Alan Ladd can still play the brusque tough guy and William Bendix steals the show with his own blue-collar bravado and snarling bluster. Veronica Lake doesn’t show up until well into the film and in many ways, despite her billing, she feels relegated to a smaller role. She’s not particularly memorable in the majority of it even with her scenes with Ladd. She’s mostly just there which is grossly unfortunate. It feels like a waste.

After the novelty of Hugh Beaumont wears off it makes sense why he transitioned to TV while Howard Da Silva and Doris Dowling denote a certain sleaze that comes off quite well. Meanwhile, Frank Faylen plays an integral role as one of his typical curmudgeon types. He made a killing off of that niche. Still, Ladd and Bendix are the main attraction in this adequate serving of film-noir. On a darker note, this film also gave its name to the unsolved Black Dahlia killing of Elizabeth Short in 1947. It’s one time when perhaps reality was more tragic than fiction. Raymond Chandler could not have even dreamed up such a grisly drama. At least not for the silver screen.

3.5/5 Stars

With Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon making a splash just the year before and giving a big leg up to its star Humphrey Bogart as well as its director John Huston, it’s no surprise that another such film would be in the works to capitalize on the success. This time it was based on Hammett’s novel The Glass Key and it would actually be a remake of a previous film from the 30s starring George Raft.

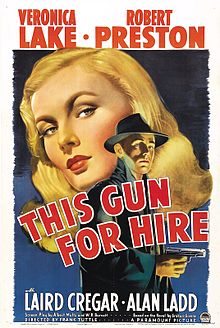

With Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon making a splash just the year before and giving a big leg up to its star Humphrey Bogart as well as its director John Huston, it’s no surprise that another such film would be in the works to capitalize on the success. This time it was based on Hammett’s novel The Glass Key and it would actually be a remake of a previous film from the 30s starring George Raft. Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake found themselves partnered together on numerous occasions partially out of convenience (at 5’6 and 4’11 they were a perfect height match) but also there’s a genuine chemistry between them. And it all came into being with This Gun for Hire an economical film-noir where Ladd wasn’t even one of the top-billed stars.

Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake found themselves partnered together on numerous occasions partially out of convenience (at 5’6 and 4’11 they were a perfect height match) but also there’s a genuine chemistry between them. And it all came into being with This Gun for Hire an economical film-noir where Ladd wasn’t even one of the top-billed stars. There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand.

There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand.

The Birds is about all sort of birds. The ones we are acquainted with initially are actually a pair of humans. Lovebirds you might call them. Except they don’t know it quite yet, but the moment Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) and Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor) meet in a pet shop, the sparks are already flying — the birds too.

The Birds is about all sort of birds. The ones we are acquainted with initially are actually a pair of humans. Lovebirds you might call them. Except they don’t know it quite yet, but the moment Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) and Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor) meet in a pet shop, the sparks are already flying — the birds too. Most assuredly, the film benefits from long stretches of wordless action. The most striking example involves a murder of crows gathering on a jungle gym near the schoolhouse. Never before was the name of their posse more applicable. And while the narrative lacks a true score, the unnerving screeches from the birds is sound enough to send chills down the spine of any audience.

Most assuredly, the film benefits from long stretches of wordless action. The most striking example involves a murder of crows gathering on a jungle gym near the schoolhouse. Never before was the name of their posse more applicable. And while the narrative lacks a true score, the unnerving screeches from the birds is sound enough to send chills down the spine of any audience. I find that my own life was greatly influenced by my father during my most formative years, in particular in the realm of music. I grew up on the classics of the ‘60s. But there’s that juncture in time perhaps during middle school where you begin to branch out and you latch onto other sounds for some inexplicable reason. And it doesn’t have to be modern artists but even those who your parents never imparted to you. That is to say that “Brandy” by Looking Glass is such a song for me. I loved it the first time I heard it and not on any provocation of my parents. I consider it one of my own personal favorites.

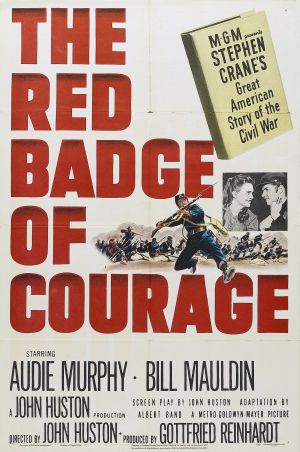

I find that my own life was greatly influenced by my father during my most formative years, in particular in the realm of music. I grew up on the classics of the ‘60s. But there’s that juncture in time perhaps during middle school where you begin to branch out and you latch onto other sounds for some inexplicable reason. And it doesn’t have to be modern artists but even those who your parents never imparted to you. That is to say that “Brandy” by Looking Glass is such a song for me. I loved it the first time I heard it and not on any provocation of my parents. I consider it one of my own personal favorites. Stephen Crane’s seminal Civil War novel was made to be gripping film material and although my knowledge of the particulars is limited John Huston’s story while streamlined and truncated feels like a fairly faithful adaptation that even takes some effort to pull passages directly from the original text.

Stephen Crane’s seminal Civil War novel was made to be gripping film material and although my knowledge of the particulars is limited John Huston’s story while streamlined and truncated feels like a fairly faithful adaptation that even takes some effort to pull passages directly from the original text. The Greek gods created a woman – Pandora. She was beautiful and charming and versed in the art of flattery. But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us.

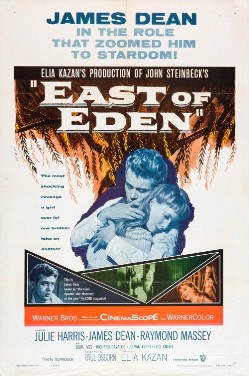

The Greek gods created a woman – Pandora. She was beautiful and charming and versed in the art of flattery. But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us. East of Eden. It was John Steinbeck’s epic work. Showcasing a familial narrative sprawled across his familiar locales of Salinas and Monterey over the turn of the century. But as a film, it rather unwittingly became James Dean’s. He wasn’t even a star yet. He had been on the stage and in a few small roles on television. His performance as Cal Trask was his first film role and the only one that ever got released during his lifetime. As his following two films, both premiered after his untimely death (curiously not all that far away from this film’s setting).

East of Eden. It was John Steinbeck’s epic work. Showcasing a familial narrative sprawled across his familiar locales of Salinas and Monterey over the turn of the century. But as a film, it rather unwittingly became James Dean’s. He wasn’t even a star yet. He had been on the stage and in a few small roles on television. His performance as Cal Trask was his first film role and the only one that ever got released during his lifetime. As his following two films, both premiered after his untimely death (curiously not all that far away from this film’s setting).