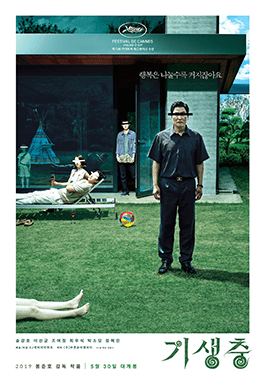

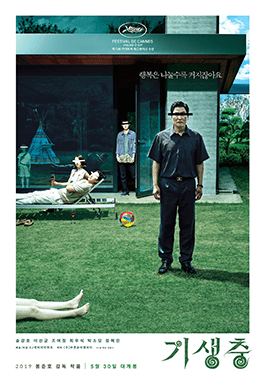

I heard in an interview director Bong Joon-ho had the idea for Parasite percolating in his mind for a long time, and it was born out of the most curious forms of inspiration. In college, he used to tutor English for the child of a rich family. From that point of disembarkation, he started asking “what if…” and all of a sudden his latest thriller was born.

Whether this story is completely true or not, it gets at what I relish about screenwriting and the inception of ideas in any form. Oftentimes they come straight out of real-life experiences only to be morphed and molded, burnished and extrapolated upon until they take on an existence entirely their own.

In some ways, Parasite feels very much related to the previous year’s Cannes darling Shoplifters, directed by Hirokazu Koreeda. In both cases, a story about an impoverished family becomes a handy jumping-off point for social commentary. But that’s just it. The premise provides a jumping-off point and there’s little else we can compare because the stories take drastically different turns simply adjudging from their creators.

Because the Kim family live crowded in a shoddy basement-dwelling leeching off the wi-fi of those who live around them, somewhat contented or at least resigned to their vagrant lifestyle. However, one day their teenage son, Ki-woo is enlisted by a friend to fill his position tutoring the daughter of a rich family.

His family helps him with the con using their skills of photoshop, composition, and dramaturgy to pull off the masquerade and ingratiate themselves. It helps that their mark is a simple-minded, trusting, and generally kind matriarch. There’s a touch of Luis Bunuel in the depiction of this rather naive and vacuous bourgeoisie family getting overrun by the lower classes.

And yet a distinction must be made here too because Bong does not altogether mock them. There is the inkling of affection for all his ensemble even as he teases them. This is one of the keys to the movie’s success. The message is not hammered home at the expense of the characters.

One thing leads to another and the household vacancies begin filling up. First, an English tutor, then an art therapy instructor, next a new chauffeur, and finally a housekeeper. If the early dynamic is a tad like Shoplifters, as Parasite gears up, I couldn’t help but feel this same pervading unease experienced throughout Jordan Peele’s Get Out. While it might seem like a curious touchstone, what both films fashion are compelling thrillers carved out of the home.

The domicile and symbol of social capital, stability, even the family unit, is turned into this perturbing space that can be easily sabotaged and infested. It doesn’t matter if the main thematic element is race or class. They can both function in an insidious manner as a source of tension throughout the picture, seeping in through the cracks. Where you can live life from the heights of privilege or sunken in the subterranean void below.

While the cat’s away the mice will play, and it’s at this point we ponder where we could possibly be headed. The Kims succeed in totally taking over the house and lounging in all its decadent luxuries. This could be the end of the story. Thankfully, we are in the hands of someone who knows full-well what they are looking to accomplish.

Part of the ingenuity of the film comes in how form follows function in this very tangible way. Because the visual and environmental disparity trickles down through the story until it emphatically erupts. The metaphor takes on a very real and concrete form throughout the picture. But for the time being, it’s all about building the mounting suspense to a crescendo.

Bong is a disciple of Hitchcock, and thus he’s taken to heart the pervasive power of dramatic irony. He can both manipulate the audience while implicating us and making us totally invested in the charade at hand.

Though Parasite does have twists — one particularly harrowing in nature — it is built out of this maintained sense of dread and tension. It only works because the director has taken us into his confidence and we know something other characters do not.

The film is also built and developed out of not only its architecture but the sound design helping to create a distinct space and also a rhythm conducive to the action. A chaotic scramble to neutralize, not a gun, but a phone with social media capabilities is the centerpiece of one memorable scene full of struggling bodies, flailing arms, and the like, choreographed to perfection.

There are certain scenes like this one where they cease to be bits of exposition and dialogue, and they feel more and more like they’re verging on visual symphony as we watch images and actions flash by with a very particular cadence. They have the force to carry us away in the moment — cutting to the music — like many of the greats have done, from Hitchcock to Scorsese.

When the Kim family is finally at their lowest point, sleeping on a gymnasium floor, their patriarch utters the film’s one line which feels like some kind of worldview tucked into a movie that otherwise functions only as a satire, if not an out-and-out black comedy. He says the best plan is no plan because nothing works out the way you mean for it to anyway. It doesn’t matter if you kill someone or commit treason. Nothing matters. Nihilism is alive and well.

Still, the beauty of this is even while Mr. Kim says these things, there is a director behind him — an artistic creator — who has more than a vision for where he will end up. There is a purpose to everything that is happening to him.

If the majority of the movie is an exhibition in Hithcockian manipulation, then the ending is suitably macabre for someone totally versed in the Master of Suspense. Bong somehow manages to be playful, shocking, thrilling, and a tad somber all in the course of the final hour. The film is lengthy; we don’t always know where it will wind up, and yet it ends up in places that continually lead to further questions. You cannot unsee it or quite forget about what we have witnessed.

Parasite has an undisputed climax and still the story continues allowing itself to sink back into a newfound despondency and the original status quo. I still cannot decide if this suits everything we have been subjected too thus far.

Although another joy of screenwriting is narrative symmetry when we can take a movie back to where it began. Because so much has happened. We have weathered so much as an audience, watching and in some perverse way, rooting for this family, only for it to end up back the way it was, under very different circumstances.

All I know is that this is one of the most wickedly sharp and ingeniously pulse-pounding movies I’ve seen in quite some time. It irks me and yet in the same instance, I cannot quite turn away.

If there is any more fruit, broader still, it will come from the phenomenal press the film has received, and in an age where acclaim still guides public opinion, like Bong said himself, maybe this can be the film to help the general public conquer their fear of subtitles. Because if Parasite‘s any indication, it wields the power to open people up to expansive avenues of cinema. This is only the tip of the iceberg.

The joy of making the leap is the realization that you are not being pulled further away from what you know. More often than not, you’re getting closer — closer to the things that feel universal — the human predilections connecting us on an intimate scale. Both the parasitic and the hospitable, the good and the evil.

Although they couldn’t be a more diverse company, you see it in Hitchcock (a Brit), Koreeda (a Japanese), Bunuel (a Spaniard), Bong (a South Korean), and many others. Go watch them if you have the chance. My hope is you will be glad you did.

4.5/5 Stars

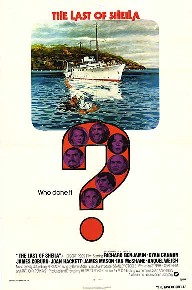

“That’s the thing about secrets. We all know stuff about each other; we just don’t know the same stuff.”

“That’s the thing about secrets. We all know stuff about each other; we just don’t know the same stuff.”

I never thought I’d be saying this about a Woody Allen film, but it feels more like a technical marvel than purely a testament to story or dialogue. Although

I never thought I’d be saying this about a Woody Allen film, but it feels more like a technical marvel than purely a testament to story or dialogue. Although